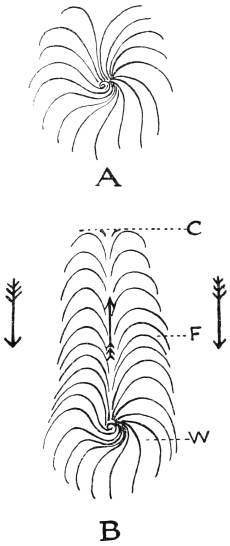

The simplest pattern consists of a reversed area of hair appearing between two adjoining streams; the more complex are whorls, featherings and crests. No detailed descrip-tion nor illustra-tion of the former are required, but I have prepared a diagram to illustrate the latter (see p. 51.) (A) shows a whorl by itself; (B) a whorl, feathering and crest. The arrows at the sides indicate the direction of the adjoining hair-streams, the arrow in the centre of (B) the direction of the reversed flow of hair.

Fig. 2.—A. Diagram of a whorl.

B. Diagram of a whorl (W) a fea-ther-ing (F) a crest (C).

An understanding of the dynamics of a hair-whorl leads quite simply to that of a feathering and crest, for the two latter are only the results of the further extension of the battle of forces concerned in the whorl itself, and the end of their conflict. A whorl marks a point in the stream of hair where two contending forces have come into collision; on the one hand the centrifugal force of growth from each hair-papilla, the rate of which has been described, and on the other a certain centripetal dynamic force which may be either that of localised friction, pressure, gravita-tion, or muscular traction, directly opposing or divergent. Thus conceived a whorl may be looked at symbolically as a written treaty between two nations, one of which has defeated the other, and actually as a proof that the contending centrifugal and centripetal forces are in the state called the balance of power. But when the centripetal force of some habitual action prevails over that of the original force of growth in the hair, a whorl becomes extended into a feathering, and the length of this, metaphorically speaking, corresponds with the duration of open fighting, and terminated by a sharp crest when another and a decisive battle has been fought. A crest may again be looked upon as a “treaty.” The whole process pictured here shows a battle followed by a treaty or truce (W) again a retreat (F) and a counter-attack (C) with a final treaty and peace.

This hypothetical treatment, with addition of some metaphors, does not carry us far enough to leave it thus to the tender mercy of that class of critic who relies too much on the “argument from ignorance.” He tells us such a process as I have pictured may be true or not, and that no one can do more than leave the case open, and treat it like that of Jarndyce & Jarndyce where it would remain in Chancery till all of us concerned in the inquiry have returned to our dust. The critic might reasonably ask for experiments which will bear out the suggested views. But verifica-tion by calculated experiments is impossible, for, ex hypothesi, the variations or patterns which are described require long periods of time for their produc-tion. Such experiments being ruled out, the evidence in favour of the hypothesis must be sought in some region of the hairy coat of mammals where whorls, featherings and crests can be observed in all stages of their formation.

The Side of the Horse’s Neck.

The field chosen for observa-tion is, from one point of view, the most remarkable among all the numerous regions in the great series of hair-clad mammals. The side of the neck in the domestic horse displays all degrees and forms of whorls, featherings and crests in such variety as to be almost bewildering. I must have examined many thousands of specimens of this valuable large mammal in reference to this state of things on the side of its neck, and can only regret that I have not kept any record of them as to number or quality, and I fear the opportunity for doing so will not return in this country. There are three reasons for this choice

of field. In the first place there is or was an extensive supply of the specimens for examina-tion; in the second, the side of a horse’s neck is a region where no extraneous or artificial agents, such as harness, except a bridle, can operate, and therefore Nature and the animal’s habits have free play; in the third the neck of a horse in its locomotive life is subject to powerful mechanical forces which are constant, literally speaking, while it walks, trots, canters or gallops. Here then, if anywhere, one may read the records, in indelible characters of hair patterns, the history of its active life and that of its ancestors, and here also one may reasonably expect to find these patterns in every possible stage of formation, from a mere rudiment to the most finished product in a whorl, feathering and crest—and this is precisely what is found to exist.

Even an observer not acquainted with the anatomy of this region who watches closely a horse in action cannot fail to notice how at every step taken there is a marked jolt of the neck produced in the neck by the impact of its hoofs with the ground and in supporting its heavy skull. I have computed several times the number of jolts that the neck of a trotting horse sustains, in my numerous rides behind various horses, during many hundreds of miles, and have reckoned the number which occur in a horse trotting for an hour, at the usual rate at which a doctor travels. This is on the average 6,000, and of course the numbers of jolts in walking, cantering, and galloping vary according to these different paces. But a great deal more of movement of the head and neck is observed beside the jolt at every step. See how the animal tosses up its head, twists it to this and that side for the mere joie de vivre when it is fresh, or, even when hindered by blinkers,47 how he turns his head to look at every passing object in the road with his ancestral caution, how he will pass contemptuously a great horse-waggon or even now a villainous-looking motor lorry, but will peer at a beggar woman sitting beside the road, or a heap of stones, or a yapping cur! All this vivid muscular work of a horse’s head and neck hardly ceases while he is in action and at any rate not till he is dead beat, and the higher the courage and breeding of the horse the more frequent and brisk are his movements. Is it possible to conceive a region of the body of any large mammal where more numerous, varied, and powerful action of underlying muscles can

be found playing their ceaseless tricks on the sober normal slope of hair in the skin which covers them? If there be any region approaching this I have not found it.

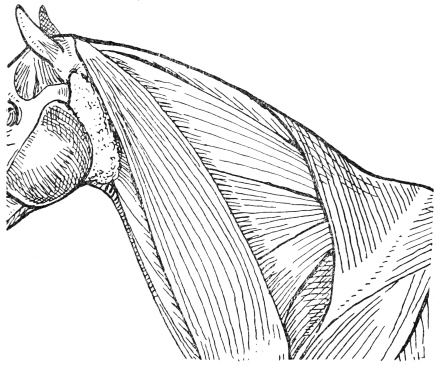

Fig. 3.—Superficial muscles concerned in the move-ments of the head and neck of the horse.

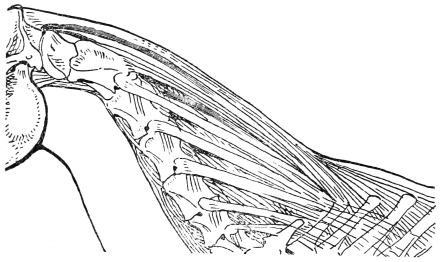

Fig. 4.—Deeper layer of the muscles concerned in the move-ments of the head and neck of the horse; the scapula removed.

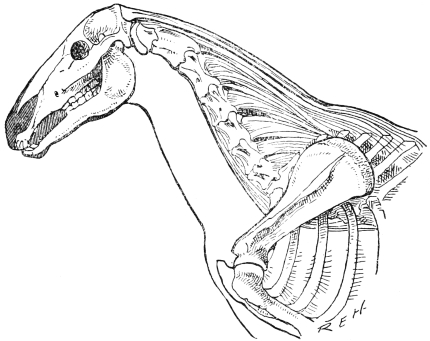

The main facts of the anatomy of the horse’s neck must be referred to here, so that a better picture may be obtained as to the powerful forces which are found in conflict during the locomotive life of the animal. Fig. 3 shows the superficial layer of muscles concerned in the actions of its head and neck, and the manner in which adjoining muscles diverge from one another should be noted. Fig. 4 gives the deepest layer of neck-muscles, the shoulder-blade having been removed, and Fig. 5 the immensely strong ligamentum nuchae, of yellow elastic tissue, which extends from the base of the skull to the great projecting spinous process of the lowest cervical and second and third dorsal vertebr?.

Fig. 5.—Ligaments and tendons supporting the head and neck of the horse.

There are here indeed great forces for conflict—first a layer of strong superficial muscles, second a layer of smaller muscles which has not been figured, third a deep layer of muscles, and fourth a powerful, widely-spread and strongly-attached mass of

dense elastic tissue, adapted for supporting the head without muscular exertion, but by its elasticity allowing a downward jerk of the head and neck at every step. It is an exceedingly important structure for a domestic horse.

The Normal Arrangement of Hair.

So much for the active part played by a horse’s neck and head, and for the simpler anatomical facts of the region involved. Before proceeding to describe the results of these as seen in the hair, it is well to make sure of a point which a critic might raise. “How do you know,” says he, “that some of the variations in this highly variable region of the hair are not normal. What is the normal type here?” A very easy answer to this is found by studying, not only any Ungulate known, except the Gnu, but more particularly all wild Equid?; and this reveals the fact that in all this series the normal slope of hair prevails here, that is to say, an even trend from head to shoulder. Variations in others, indeed, hardly exist, and I may add that the absence of variations here is a strong piece of negative evidence in my favour, for no Ungulate comes near the domestic horse for amount and activity of locomo-tion, which is indeed his raison d’être. He is the only one that has invented new patterns. But a little direct evidence can be brought which clinches this argument from inference based on ancestry. I made an examina-tion, at the stables of Messrs. Tilling, at Peckham, of 100 consecutive specimens of hackney, for the purpose of ascertaining the propor-tion in that group of those that showed the normal slope on the neck to those with variations. In 62 of these the normal existed on both sides of the neck, 18 Normal on one side, and in the remaining 20 there were variations on both sides. If 100 specimens of horses contain 80 with one side and 62 with both normal the previous inference requires no further support.

Fourteen Varieties.

I have put together here, and described, fourteen out of a much larger number of the most instructive varieties of pattern that I have been able to collect during the course of many years and examina-tion of several thousand horses. They comprise examples the mostly likely, as I think, to convey to the reader an adequate picture of the results of the strength, number and variety of mechanical forces in our present battle-field of hair. The diagrams almost speak for themselves, but a short written descrip-tion will help to emphasise the salient points.

There are pictured here the normal type, divergent hair-streams partially reversed, simple whorls in different regions, a whorl and feathering, whorls, featherings and crests, and these in several areas. It is a veritable portrait gallery in which is portrayed the earliest and latest stages of this family of fashions in hair on the horse’s neck. They are grouped mostly in pairs.

Fig. 6.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Normal type, hair-stream passing evenly in line of neck.—Bay hack-ney, examined 3rd May, 1904.

Fig. 7.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Complete whorl with wide feathering which ex-tends from base of the neck to the ear where it ends in a crest.—W.F.C.

Brown hackney, examined 12th January, 1904.

Fig. 6 shows the normal slope and by its side Fig. 7 gives a view of the best specimen of a completed whorl, feathering and crest I have been able to examine, the whole length of the neck being occupied by it. So in this pair the normal and most extensive departure from it lie side by side.

Fig. 8.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Offside, anterior portion of neck showing line of di-vi-sion, B to A, along up-per bor-der of sterno-mastoid muscle, nor-mal arrange-ment from A to C.

Grey pony, examined 15th December, 1903.

Fig 9.—Side of Neck in Horse.

Near side, winter coat, showing nor-mal ar-range-ment from B to A, where a division begins and ex-tends along up-per bor-der of ster-no-mas-toid muscle to base of neck.

Brown hackney, examined 28th December, 1903.

Fig. 8 shows the way in which two streams of hair close up to the ears begin to diverge. Fig. 9 a similar divergence towards the base of the neck.

Fig. 10.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Line of division of streams curving upwards to the mane near the base of the neck.

Chestnut cart horse, examined 9th December, 1903.

Fig. 11.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Near side, line of division along the up-per bor-der of ster-no-mas-toid muscle di-vert-ed at C towards the mane.

Bay cart horse, examined 11th December, 1903.

Fig. 10 gives not only a divergence, but a well-marked turn in the upper hair-stream and Fig. 11 the way in which this divergent turn of hair is being converted into a feathering.

Fig. 12.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Near side, at C upward curve towards mane. Brownish-yellow hackney, examined 18th August, 1903.

The same horse as appears in Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.—Side of Neck of Horse—same spe-ci-men as in Fig. 12.

Offside, fully developed whorl, feathering and crest W, F, C, lying along upper border of ster-no-mas-toid muscle. Two stages of for-ma-tion of this form of pat-tern in one spe-ci-men.

Brownish-yellow hackney, examined 18th August, 1903.

Fig. 12 presents a stream of hair still more twisted from its course than that of Fig. 10, and Fig. 13 a whorl going on to a feathering which loses itself, without coming to an abrupt stop in a crest which is the more usual course.

Fig. 14.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Near side, whorl (W) in place of common line of di-vi-sion, with wide for-ward fea-ther-ing to A, where the hair streams di-verge sharply.

Brown hackney, examined 19th November, 1903.

Fig. 15.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Near side, showing (B to C1) diversion of hair stream towards mane (W1F1C1) whorl, fea-ther-ing and crest; W1 to W2 stream in normal di-rec-tion W2 a sec-ond whorl.

Chestnut cart horse, examined 1st January, 1904.

Fig. 14 is a common type of whorl, feathering and crest in the most usual situation. Fig. 15 a rarer and more complicated instance of a simple whorl, a gap and then a whorl, feathering and crest in the same “critical area.”

Fig. 16.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Near side (W1F1C1) showing whorl, fea-ther-ing and crest along up-per line of di-vi-sion (W2F2C2) a sec-ond fully-formed whorl, fea-ther-ing and crest, cross-ing both up-per and lower lines of di-vi-sion, and end-ing at W1. Grey pony, exam-ined 23rd May, 1903.

Fig. 17.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Near side (W1F1C1) whorl, fea-ther-ing and crest, fully-formed, cut-ting up-per line of di-vi-sion at ob-tuse angle and a sec-ond whorl, fea-ther-ing and crest (W2F2C2) along an-ter-ior part of com-mon line of di-vi-sion. Roan hack-ney, exam-ined 7th November, 1903.

Fig. 16 and Fig. 17 are rare cases of irregularly placed double whorls, featherings and crests, and give evidence of unusually complicated traction of adjoining muscles underneath this battle-field of hair.

Fig. 18.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Off side, simple whorl, behind ear at edge of mane.

Fig. 19.—Side of Neck of Horse.

Simple whorl (W) at edge of mane midway between ears and base of neck.

Figs. 18 and 19 show a simple whorl, situated at the very edge of the mane, a very “critical” area because this looser and heavy part of the neck is very much subject to jolting during the horse’s action.

I have little to add to the graphic evidence afforded by these pictures, each of which I observed noted and sketched as the bearers of them came before me during many years of a “Captain-Cuttle-like” disposal of some of my leisure. No clearer proof can be desired of the view here advanced, that habit or habitual muscular action, and jolting, is the cause of the varied patterns in this field, and that according to the Law of Parcimony no other is required, this canon of Occam being expressed more succinctly—Neither more, nor more onerous causes are to be assumed than are necessary to account for the phenomena.