‘To Master John, the English maid

A horn-book gives, of gingerbread;

And, that the child may learn the better,

As he can name, he eats the letter.’

It was made with honey, before the introduction of sugar, and must be of remote antiquity and intimately allied to our friend the Bous. The Rhodians made bread with honey which was so pleasant that it was eaten as cake after dinner. The German gingerbread and the French pain d’épice used both to be made with honey. The use of gingerbread is widely spread, and wherever it is eaten it is popular, even in the far East Indies, where both natives and Anglo-Indians rejoice in it. In Holland it is in more request than in any other country in Europe, and the recipe152 for its manufacture is guarded as a jealous secret and descends as an heirloom from father to son.

In its early days gingerbread was an unleavened cake, and the first attempt to make it light was to introduce pearl-ash or potash; afterwards alum was introduced, now it is made of ordinary fermented dough, or with carbonate of ammonia. When well made, gingerbread will last good for years; but if not well made, and of good materials, it will last no time,153 but will get soft with the first damp weather. Such was the stuff sold at fairs—both thick gingerbread and nuts—booths being erected for the sale of nothing else. The background of these booths was ornamented by gingerbread crowns, kings and queens, cocks, etc., dazzlingly resplendent with pseudo gold leaf, or, as it was then called, ‘Dutch metal.’ I do not think that anybody ever ate any of these works of art, I think they were solely for ornament; and, when combined with bows and streamers of bright-coloured ribbons, they made the gingerbread booths the most attractive in the fair.

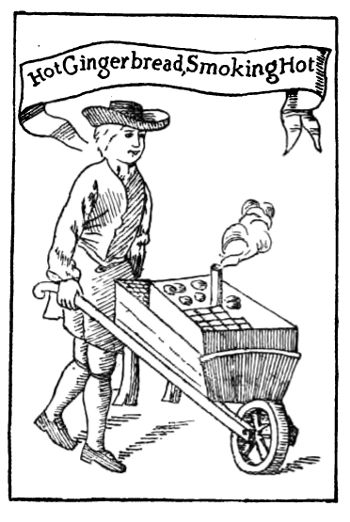

In the last century it was a great institution, and Swift, writing to Stella, says: ‘’Tis a loss you are not here, to partake of three weeks’ frost, and eat gingerbread in a booth by a fire on the Thames.’ There was a famous itinerant vendor of this article named Ford, but who was more generally known as ‘Tiddy Diddy Doll,’ from a song he used to sing whose words were but those. He flourished in the middle of last century, and Hogarth painted him in one of the scenes of ‘Industry and Idleness,’ where the idle apprentice is going to his doom.

Hogarth’s Picture of Ford.

Hone, in his Every Day Book, vol. i., p. 375, etc., gives a very good account of Ford. He says: ‘This celebrated vendor of gingerbread, from his eccentricity of character, and extensive dealings in his way, was always hailed as the king of itinerant tradesmen.17 In his person he was tall, well made, and his features handsome. He affected to dress like a person of rank—white and gold suit of clothes, 154

155laced ruffled shirt, laced hat and feathers, white silk stockings, with the addition of a fine white apron. Among his harangues to gain customers, take this as a specimen: ‘Mary, Mary, where are you now, Mary? I live, when I am at home, at the second house in Little Ball Street, two steps underground, with a wiscum, riscum, and a why-not. Walk in, ladies and gentlemen, my shop is on the second floor backwards, with a brass knocker at the door. Here’s your nice gingerbread, your spice gingerbread; it will melt in your mouth like a red-hot brick-bat, and rumble in your inside like Punch and his wheel-barrow.’... For many years (and perhaps at present) allusion was made to his name, as thus: ‘You are so fine, you look like Tiddy Doll. You are as tawdry as Tiddy Doll. You are quite Tiddy Doll,’ etc.

But there is a use for badly-made gingerbread which perhaps some of us do not know—a gingerbread barometer. It is nothing more than the figure of a General made of gingerbread, which Clavette buys every year at the Place du Trone. When he gets home he hangs his purchase on a nail. You know the effect of the atmosphere on gingerbread; the slightest moisture renders it soft; in dry weather, on the contrary, it grows hard and tough. Every morning, on going out, Clavette asks his servant, ‘What does the General say?’ The man forthwith applies his thumb to the figure, and replies, ‘The General feels flabby about the chest; you’d better take your umbrella!’ On the other hand, when the symptoms are hard and156 unyielding, our worthy colleague sallies forth in his new hat.

A curious use of dough, somewhat sweetened, was made at Christmas, when it was manufactured into Yule doughs, or dows, or Yule babies, small images like dolls with currants for eyes, intended probably to represent the infant Jesus, which were presented by bakers to the children of their customers. Another Christmas custom connected with dough used to obtain in Wiltshire, where a hollow loaf, containing an apple, and ornamented on the top with the head of a cock or a dragon, with currant eyes, and made of paste, was baked, and put by a child’s bedside on Christmas morning to be eaten before breakfast. This was called a Cop-a-loaf, or Cop-loaf.

Much land in England was held by tenure, in which bread plays a part, as the following instances out of many will show.18

Apelderham, Sussex.—John Aylemer holds by court roll one messuage and one yard [thirty acres] land.... And he ought to find at three reap days, in autumn, every day, two men, and was to have for each of the said men, on every of such reap days, viz., on each of the two first days, one loaf of wheat and barley mixed, weighing eighteen pounds of wax, every loaf to be of the price of a penny farthing; and at the third reap day each man was to have a loaf of the same weight, all of wheat, of the price of a penny halfpenny.

Chakedon, Oxon.—Every mower on this manor 157was to have a loaf of the price of a halfpenny, besides other things.

Glastonbury, Somerset.—In the thirty-third year of Edward I., William Pasturell held twelve ox-gangs of land there from the abbot, by service of finding a cook in the kitchen of the said abbot and a baker for the bakehouse.

Hallaton, Leicester.—A piece of land was bequeathed to the use and advantage of the rector, who was there to provide ‘two hare pies, a quantity of ale, and two dozen of penny loaves, to be scrambled for on Easter Monday annually.’

Lenneston or Loston, Devon.—Geoffrey de Alba-Marlia held this hamlet of the King, rendering therefore to the King, as often as he should hunt in the Forest of Dartmoor, one loaf of oat bread of the value of half a farthing, and three barbed arrows, feathered with peacock’s feathers, and fixed in the aforesaid loaf.

Liston, Essex.—In the forty-first year of Edward III., Nan, the wife of William Leston, held the manor of Overhall, in this parish, by the service of paying for, bringing in, and placing of five wafers before the King, as he sits at dinner, upon the day of his coronation.

Twickenham, Middlesex.—There was an ancient custom here of dividing two great cakes in the church among the young people on Easter Day; but, it being looked upon as a superstitious relic, it was ordered by Parliament, in 1645, that the parishioners should forbear that custom, and instead thereof buy loaves of bread for the poor of the parish with the money that158 should have bought the cakes. It is probable that the cakes were bought at the vicar’s expense; for it appears that the sum of one pound per annum is still charged upon the vicarage for the purpose of buying penny loaves for poor children on the Thursday before Easter. Within the memory of man they were thrown from the church steeple to be scrambled for.

Wells, Dorset.—Richard de Wells held this manor ever since the Conquest by the service of being baker to our Lord the King.

Witham, Essex.—By an inquisition made in the reign of Henry III., it appears that one Geoffrey de Lyston held land at Witham by the service of carrying flour to make wafers on the King’s birthday, whenever his Majesty was in the Kingdom.

Of bread, as given away in charity or by dole, the examples in England are almost numberless; still a few somewhat redeemed from common place, and extracted from the Report on Charities, may interest the reader.19

Assington, Suffolk.—John Winterflood, by will dated April 2, 1593, gave to the poor of Assington four bushels of meslin (wheat and rye) payable out of the manor of Aveley Hall, to be distributed in bread at Christmas; and four bushels of meslin, out of the rectory or priory of Assington, to be distributed in bread at Easter; and under this donation four bushels of wheat are brought to Assington Church and distributed among the poor at Christmas, and the like quantity of wheat at Easter.

159

St. Bartholomew by the Exchange, London.—Several benefactors have given bread to the poor of this parish. Richard Crowshaw, goldsmith, by will, April 26, 1531, directed that 100l. should be paid to provide 2s. weekly for ever, to be laid out in good cheese, to be delivered to the poor parishioners of this parish, according as they received the bread, which then was and had been long given them.

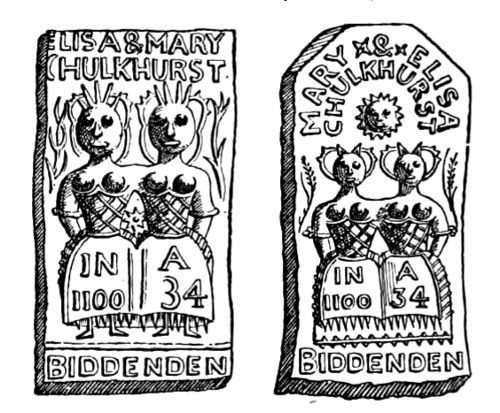

The Biddenden Maids.

Another bread and cheese charity still obtains in the village of Biddenden, Kent, about four miles from Tenterden; and it is noticeable on account of the160 tradition which assigns its foundation to a lusus natur? similar to the Siamese twins of our day. The founders of the charity, according to tradition, were Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst, who were born in 1100, and lived together, joined at hips and shoulders, for 34 years. To perpetuate their memory, biscuits, measuring 3-1/2 in. by 2 in. and about 1/4 in. thick, are made and distributed with the dole of bread on Easter Sunday. On these biscuits is stamped a rude representation of the ‘Biddenden Maids.’ There are two moulds, one made of beech-wood, judging from the twins’ costume of commode, or cap, and laced bodice, dates from the time of William and Mary or Anne; the other, which is of boxwood, although an attempted copy, is undoubtedly more modern. The writer has the biscuits, and with them came the following paper, headed by a rough woodcut:

‘A short and concise history of Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst, who were both joined together by the hips and shoulders, in the year of our Lord 1100, at Biddenden, in the County of Kent, commonly called “The Biddenden Maids.”’

The reader will observe by the plate that they lived together in the above state 34 years, at the expiration of which time one of them was taken ill, and in a short time died; the surviving one was advised to be separated from the body of her deceased sister by dissection, but she absolutely refused the separation by saying these words, ‘As we came together we will also go together’; and in the space of about six hours after her sister’s decease she was taken ill and died also.

161

By their will they bequeathed to the churchwardens of the parish of Biddenden and their successor churchwardens, for ever, certain pieces or parcels of land in the parish of Biddenden, containing 20 acres, more or less, which are now let at 40 guineas per annum. There are usually made, in commemoration of these wonderful phenomena of Nature, about 1000 rolls (sic) with their impressions printed on them, and given away to all strangers on Easter Sunday, after Divine Service in the afternoon; also about 500 quartern loaves, and cheese in proportion, to all the poor inhabitants of the said parish.

Hasted, in his History of the County of Kent (edit. 1790, Vol. III., p. 66), says, with regard to this benefaction: ‘There is a vulgar tradition in these parts that the figures on the cakes represent the donors of this gift, being two women—twins—who were joined together in their bodies, and lived together so till they were between 20 and 30 years of age. But this seems without foundation. The truth seems to be that it was the gift of two maidens of the name of Preston, and that the print of the women on the cakes has only taken place within these 50 years, and was made to represent two poor widows, as the general objects of a charitable benefaction. William Horner, rector of this parish, in 1656, brought a suit in the Exchequer for the recovery of these lands, as having been given for an augmentation of his glebe land; but he was nonsuited.’