The shrieks of Persephone were heard only by Hecate and Helios; and her mother, hearing only the echo of her voice, at once darted down to earth in search of her beloved child. Hopelessly and aimlessly she wandered about, caring nothing for herself; and for nine whole days and nights neither ate nor drank, tasted neither nectar nor ambrosia, nor did she even bathe herself. On the tenth day she met Hecate, who44 told her all she knew of her daughter’s disappearance, which was not much, as she had heard but her piercing cries. But, thinking that Helios, the all-seeing sun, might have viewed the scene, they hastened to him, and he told them how it all happened: how Pluto had carried off her daughter, with the approval and consent of Zeus.

Heart-broken at this conduct of the father of her child, she would have no more of the society of the gods, and forswore Olympus, preferring to live rather among men on earth. And so she dwelt among them, rewarding those who were kind to her and severely punishing those who did not treat her well; and in this way, still wandering and mourning for her lost child, she came to Eleusis, where Celeus was king.

But her wrath was still as fierce as ever, and, by withholding her gifts, the fields produced no crops, and there was famine upon earth, and so sore indeed did it become that Zeus, perceiving it, feared that the race of man might become extinct for lack of food, and sent Iris as ambassador to try and persuade Demeter to return to Olympus. But she was firm, although all the gods were sent to her to induce her to relent, and nothing would she do to mitigate the evil she had wrought, save on the condition that her daughter should be restored to her.

The Legend of Demeter and Triptolemus.

Hermes was sent to Pluto, and his mission met with partial success. Persephone had eaten of the pomegranate seed, which sacredly pledged her to her dread lord; and for three months in the year she must leave her mother and the fair earth and go to45 live in Pluto’s dreary kingdom. Hermes fulfilled his mission by restoring her to her loving mother, who rejoiced over her with an exceeding joy. Zeus, choosing this happy moment, sent Rhea to Demeter to conciliate her and prevail upon her to return to Olympus—a task which she happily effected. The earth smiled once more and became fertile, and Demeter, with her daughter, to whom she was lent for nine months in the year, went to dwell once more in the companionship of the gods; but, before she left the earth, she rewarded Celeus, the King of Eleusis, who had been kind to her, by giving his son, Triptolemus, a chariot with winged dragons and seeds of wheat. His chariot was useful, for by means of it he was able to ride all over the earth, and46 instruct men in growing corn. He established the worship of Demeter at Eleusis, and instituted the mysteries in honour of the goddess.

And in this pretty myth of Demeter and Persephone we may trace the story of the seasons; how for nine months the earth is smiling and fertile, and for the remaining three is dead.

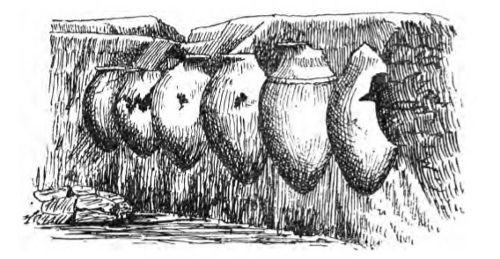

Dr. Schliemann claimed to have found the site of ancient Troy when he uncovered the hill of Hissarlik. It was undoubtedly the remains of a pre-historic city, and one which had advanced to a considerable amount of civilisation. And this is shown particularly in one instance, in the huge earthenware jars, or pithoi, that were used for storing corn and wine. The following illustration gives a graphic description of them as they appeared in situ: ‘One of the compartments of the uppermost houses below the Temple of Athené, and belonging to the third, the burnt city, appears to have been used as a magazine for storing corn or wine, for there are in it nine enormous earthenware jars of various forms, about 5 ft. high and 4-3/4 ft. across, their mouths being from 29-1/2 in. to 35-1/4 in. broad. Each of them has four handles 3-3/4 in. broad, and the clay of which they are made is as much as 2-1/4 in. thick.’7

Dr. Schliemann says [p. 279]: ‘The number of large jars which I brought to light in the burnt stratum of the third city certainly exceeds 600. By far the larger number of them were empty, the mouth being covered by a large flag of schist or limestone. This leads me to the conclusion that the jars were 47filled with wine or water at the time of the catastrophe, for there appears to have been hardly any reason for covering them if they had been empty. Had they been used to contain anything else but liquids, I should have found traces of the fact, but only in a very few cases did I find some carbonised grain in the jars, and only twice a small quantity of a white mass, the nature of which I could not determine.’

Pithoi found at Hissarlik.

So that we see that this pre-historic nation not only grew corn, but stored it for future use.

The means this pre-historic people had of crushing or mealing the grain was the same as usual: the saddle querns, or two stones with flat surfaces, between which the grain was crushed and roughly triturated—so frequently found on the Continent, and the pestle and mortar of the lake dwellings, as also round stones for fitting into hollows such as are found in the lakes, the cave dwellings of the Dordogne and in the48 dolmens of France. Dr. Schliemann, in describing ‘the Trojan saddle querns,’ says they ‘are either of trachyte or of basaltic lava, but by far the larger number are of the former material. They are of oval form, flat on one side and convex on the other, and resemble an egg cut longitudinally through the middle. Their length is from 7 in. to 14 in., and even as much as 25 in.; the very long ones are generally crooked longitudinally, their breadth is from 5 in. to 14 in. The grain was bruised between the flat sides of two of these querns; but only a kind of groats can have been produced in this way, not flour. The bruised grain could not have been used for making bread. In Homer we find it used for porridge (Il. xviii., 558-560), and also for strewing on the roasted meat (Od. xiv., 76-77).’

In Homeric times the corn was evidently ground by millstones (which were, probably, precisely similar to those found by Dr. Schliemann), as we see in Il. vii. 270, xii., 161, and Od. vii., 104, xx., 105. Pliny N.H., xxxvi., 30, speaking of millstones says: ‘In no country are the molar stones superior to those of Italy; stones, be it remembered, not fragments of rock; there are some provinces, too, where they are not to be found at all. Some stones of this class are softer than others, and admit of being smoothed with the whetstone, so as to present all the appearance, at a distance, of serpentine. There is no more durable stone than this; for, in general, stone, like wood, suffers from the action, more or less, of rain, heat, and cold.... Some persons give this molar stone the49 name of pyrites, from the circumstance that it has a great affinity to fire.’

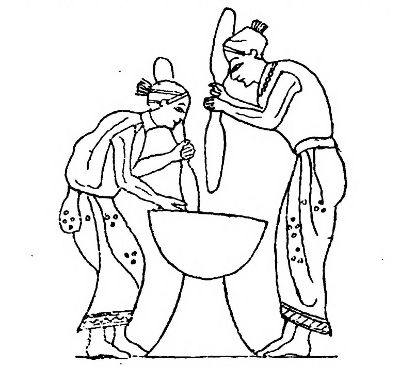

Pounding Grain.

In book xviii., 23, Pliny gives us the mode of grinding corn. ‘All the grains are not easily broken. In Etruria they first parch the spelt in the ear, and then pound it with a pestle shod with iron at the end. In this instrument the iron is notched at the bottom, sharp ridges running out like the edge of a knife, and concentrating in the form of a star, so that, if care is not taken to hold the pestle perpendicularly while pounding, the grains will only be splintered and the iron teeth broken. Throughout the greater part of Italy, however, they employ a pestle that is only rough at the end, and wheels turned by water, by means of which the corn is gradually ground. I shall here set forth the opinions given by Mago as to the50 best method of pounding corn. He says that the wheat should be steeped first of all in water, and then cleaned from the husk, after which it should be dried in the sun and then pounded with the pestle; the same plan, he says, should be adopted in the preparation of barley.’

This was how corn was prepared in some parts of Italy at the time of the Christian era, by the same method as that described by Livingstone: ‘The corn is pounded in a large wooden mortar, like the ancient Egyptian one, with a pestle six feet long and about four inches thick. The pounding is performed by two or even three women at one mortar. Each, before delivering a blow with her pestle, gives an upward jerk of the body, so as to put strength into the stroke, and they keep exact time, so that two pestles are never in the mortar at the same moment.... By the operation of pounding, with the aid of a little water, the hard outside scale or husk of the grain is removed, and the corn is made fit for the millstone. The meal irritates the stomach unless cleared from the husk; without considerable energy in the operation the husk sticks fast to the corn. Solomon thought that still more vigour than is required to separate the hard husk or bran from the wheat would fail to separate “a fool from his folly.” “Though thou shouldest bray a fool in a mortar among wheat with a pestle, yet will not his foolishness depart from him.”’

Pounding Grain.

In book xviii., 23, Pliny gives us the mode of grinding corn. ‘All the grains are not easily broken. In Etruria they first parch the spelt in the ear, and then pound it with a pestle shod with iron at the end. In this instrument the iron is notched at the bottom, sharp ridges running out like the edge of a knife, and concentrating in the form of a star, so that, if care is not taken to hold the pestle perpendicularly while pounding, the grains will only be splintered and the iron teeth broken. Throughout the greater part of Italy, however, they employ a pestle that is only rough at the end, and wheels turned by water, by means of which the corn is gradually ground. I shall here set forth the opinions given by Mago as to the50 best method of pounding corn. He says that the wheat should be steeped first of all in water, and then cleaned from the husk, after which it should be dried in the sun and then pounded with the pestle; the same plan, he says, should be adopted in the preparation of barley.’

This was how corn was prepared in some parts of Italy at the time of the Christian era, by the same method as that described by Livingstone: ‘The corn is pounded in a large wooden mortar, like the ancient Egyptian one, with a pestle six feet long and about four inches thick. The pounding is performed by two or even three women at one mortar. Each, before delivering a blow with her pestle, gives an upward jerk of the body, so as to put strength into the stroke, and they keep exact time, so that two pestles are never in the mortar at the same moment.... By the operation of pounding, with the aid of a little water, the hard outside scale or husk of the grain is removed, and the corn is made fit for the millstone. The meal irritates the stomach unless cleared from the husk; without considerable energy in the operation the husk sticks fast to the corn. Solomon thought that still more vigour than is required to separate the hard husk or bran from the wheat would fail to separate “a fool from his folly.” “Though thou shouldest bray a fool in a mortar among wheat with a pestle, yet will not his foolishness depart from him.”’

Roman Methods of Bread-Making.

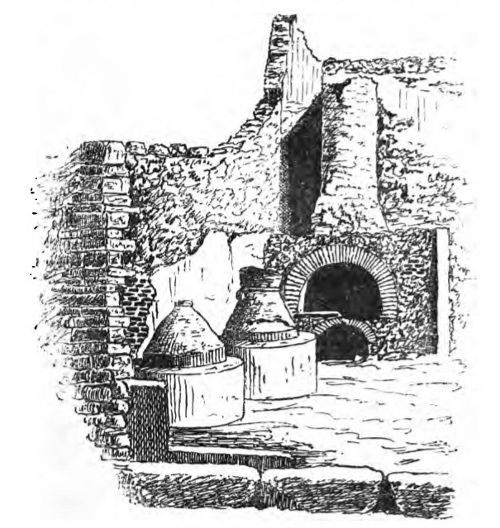

A Baker’s Shop at Pompeii.

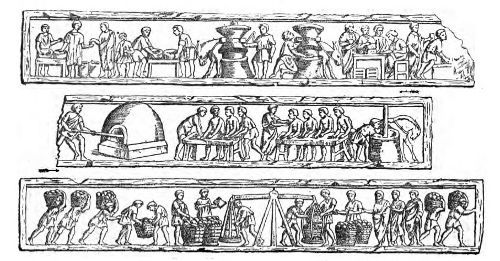

This, at all events, seems to have been the shape in vogue about the time of the Christian era; but in the bas reliefs on the tomb of Eurysaces, who was a baker in a large way of business at Rome, they seem to be globular. These bas reliefs are most interesting, as they show the whole history of baking. First there is the purchase of the corn, and payment being made for it; then we see it ground, and sifted to separate the bran. Next a man is buying some flour. Then we see the dough being kneaded by horse-power, the bakers making it into loaves, the baker with his peel baking the loaves, which are afterwards carried in55 paniers to be weighed. Then there are the customers, and the bread being sent out for delivery.

Pliny tells us that there were no bakers at Rome until the war with King Perseus of Macedon, more than 580 years after the building of the city. The ancient Romans used to make their own bread, it being an occupation which belonged to the women, as we see is the case in many nations even at the present day. In those times they had no cooks in the number of their slaves, but used to hire them for the occasion from the market. The Gauls were the first to employ the bolter that is made of horse-hair; while the people of Spain made their sieves and meal dressers of flax, and the Egyptians of papyrus and rushes.

Many freedmen were engaged as bakers, and under the Republic it was one of the duties of the ?diles to see that the bread was properly prepared and correct in weight. Grain was delivered into public granaries by enrolled Saccarii, and it was distributed to the bakers by a corporation called the Catabolenses. A bakers’ guild (corpus or collegium pistorum), which long existed, was organised by Trajan, and this body, through its connection with the cura amon?, became of much importance, and enjoyed various privileges. There were guilds of pistores and clibanarii at Pompeii. A great increase in the number of bakeries (pistrin?, officin? pistori?) afterwards took place at Rome, owing, probably, to the action of Aurelian in introducing a daily distribution of bread, instead of the old monthly distribution of grain that had been usual since the time of Gracchi.