This ceremony, which originated more than 2000 years ago, had been discontinued by degenerate princes, but was revived by Yong-tching, the third of the Mantchoo dynasty. This anniversary takes place on the 24th day of the second moon, coinciding with our month of February. The monarch prepares himself for it by fasting three days; he then repairs to the appointed spot with three princes, nine presidents of the high tribunals, forty old and forty young husbandmen. Having performed a preliminary sacrifice of the fruits of the earth to Shang-ti, the supreme deity, he takes in his hand the plough, and makes a furrow of some length, in which he is followed by the princes and other grandees. A similar course is observed in sowing the field, and the operations are completed by the husbandmen.

57

An annual festival in honour of Agriculture is also celebrated in the capital of each province. The governor marches forth, crowned with flowers, and accompanied by a numerous train, bearing flags adorned with agricultural emblems and portraits of eminent husbandmen, while the streets are decorated with lanterns and triumphal arches.

Although rice is the staple grain in use in China, wheat-growing is one of the principal industries in the northern and middle parts of that country. The winter wheat is planted at about the same time that wheat is planted here. The soil, especially in the northern provinces, is so well worn that it is unfitted for wheat-growing, and the Chinese farmers, appreciating this fact, and the fact that all kinds of fertilisers are excessively dear, make the least money do the most good by mixing the seed with finely-prepared manure.

A man with a basket swung upon his shoulders follows the plough, and plants the mixture in large handsful in the furrows, so that when the crop grows up it looks like young celery. Immediately after the first melting of snow, and when the ground has become sufficiently hardened by frost, these wheat-fields are turned into pastures, under the theory that, by a timely clipping of the tops of these plants, the crops will grow up with additional strength in the spring.

Wheat-threshing is the principal interest in Chinese farming. Owing to the scarcity of fuel, the wheat is usually pulled up by the root, bundled in sheaves, and carted to the mien-chong, a smooth and hardened58 space of ground near the home of the farmer. The top of the sheaves is then clipped off by a hand machine. The wheat is then left in the mien-chong to dry, whilst the headless sheaves are piled in a heap for fuel or thatching. When the wheat is thoroughly dry it is beaten under a great stone roller pulled by horses, while the places thus rolled are constantly tossed over with pitchforks. The stalks left untouched by the roller are threshed with flails by women and boys. The beaten stalks and straws are then taken out by an ingenious arrangement of pitchforks, and the chaff is removed by a systematic tossing of the grain into the air until the wind blows every particle of chaff or dust out of the wheat. Even the chaff is carefully swept up and stowed away for fuel or other useful purposes, such as stuffing mattresses or pillows. After the wheat is allowed to dry for a few hours in the burning sun, it is stowed away in airy bamboo bins.

The milling process is a very ancient one. Two large round bluestone wheels, with grooves neatly cut in the faces on one side, and in the centre of the lower wheel a solid wooden plug is used. The process of making flour out of wheat by this machinery is called mob-mien. Usually a horse or mule is employed; the poor, having no animals, grind the grain themselves.

Three distinct qualities of flour are thus produced. The shon-mien, or A grade, is the first siftings; the nee-mien, or second grade, is the grindings of the rough leavings from the first siftings, which is of a darker and redder colour than the first grade; and mod is the finely-ground last siftings of all grades.59 When bread is made from this grade it resembles rough gingerbread. This is usually the food of the poorest families. The bread of the Chinese is usually fermented, and then steamed. Only a very small quantity is baked in ovens. But the staple articles of food in Northern China are wheat, millet, and sweet potatoes. Wheat and rice are the food of the rich, while the middle classes of the Empire eat millet and rice. In the southern provinces the entire bread-stuff is rice.

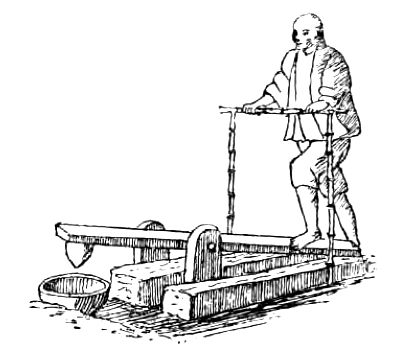

Chinese Method of Husking Grain.

At King-Kiang wheat is served as rice. It is first threshed with flails made of bamboo, and then pounded by a rough stone hammer, working in a mortar which rests on a pivot, and is operated like a treadle by the human foot. This separates the husks, and it is then winnowed, the grain being afterwards ground in the usual way.

60

Rice is undoubtedly the staple food of those parts of China where it will grow, in spite of its being a precarious crop, the failure of which means famine. A drought in its early stages withers it, and an inundation, when nearly ripe, is equally destructive; whilst the birds and locusts, which are fearfully numerous in China, infest it more than any other grain. Rice requires not only intense heat, but moisture so abundant that the field in which it grows must be repeatedly laid under water. These requisites exist only in the districts south of the Yang-tse Kiang (the Yellow River) and its several tributaries. Here a vast extent of land is perfectly fitted for this valuable crop. Confined by powerful dykes, these rivers do not generally, like the Nile, overflow and cover the country; but by means of canals their waters are so widely distributed that almost every farmer, when he pleases, can inundate his field. This supplies not only moisture, but a fertilising mud or slime, washed down from the distant mountains. The cultivator thus dispenses with manure, of which he labours under a great scarcity, and considers it enough if the grain be steeped in liquid manure.

The Chinese always transplant their rice. A small space is enclosed, and very thickly sown, after which a thin sheet of water is led or pumped over it; in the course of a few days the shoots appear, and when they have attained the height of six or seven inches the tops are cut off, and the roots transplanted to a field prepared for the purpose, when they are set in rows about six inches from each other. The whole61 surface is again supplied with moisture, which continues to cover the plants till they approach maturity, when the ground is allowed to become dry.

The first harvest is reaped in the end of May or beginning of June, the grain being cut with a small sickle, and carried off the field in frames suspended from bamboo poles placed across a man’s shoulders. Barrow (p. 565) thus describes one: ‘The machine usually employed for clearing rice from the husk, in the large way, is exactly the same as that now used in Egypt for the same purpose, only that the latter is put in motion by oxen and the former commonly by water. This machine consists of a long horizontal axis of wood, with cogs, or projecting pieces of wood or iron, fixed upon it at certain intervals, and it is turned by a water-wheel. At right angles to this axis are fixed as many horizontal levers as there are circular rows of cogs; these levers act on pivots that are fastened into a low brick wall, but parallel to the axis and at the distance of about two feet from it. At the further extremity of each lever, and perpendicular to it, is fixed a hollow pestle, directly over a large mortar of stone or iron sunk into the ground; the other extremity extending beyond the wall, being pressed upon by the cogs of the axis in its rotation, elevates the pestle, which by its own gravity falls into the mortar. An axis of this kind sometimes gives motion to 15 or 20 levers.’

Meantime the stubble is burnt on the land, over which the ashes are spread as its only manure; a second crop is immediately sown, and reaped about the end of October, when the straw is left to putrify62 on the ground, which is allowed to rest till the commencement of the ensuing spring.

As the cereal food of the Chinese is principally boiled rice, it stands to reason that bakers are not numerous, bread only appearing at the tables of high-class mandarins. It is chiefly replaced by fancy biscuits and numberless kinds of pastry, made not only with wheaten flour, but also that of rice—these serve as vehicles for the various jams and fruit compotes for which the Chinese are famous, and which they know so well how to make; in fact, the bakers are more strictly confectioners, and they can be seen any day busy in their shops baking cakes of rice flour and ground almonds of every imaginable shape and varied in quality by spices. Not only so, but these cakes are sold, already baked, in the peripatetic cookeries which go about the streets. Out of wheaten flour they make a kind of vermicelli, which is much esteemed by the Chinese.

Failure of the rice crops, and consequent famine in Japan, have been the means of introducing wheaten flour into this country more rapidly than anything else could have done. Most remarkable is the universal favour that bread and similar floury concoctions are beginning to enjoy in the treaty ports. This article of food has become completely Japanized, and sells in forms unknown to Europeans. Tsuke-pau, sold by peripatetic vendors, who push their wares along in a tiny roofed hand-cart, is much liked by the poorer classes. It consists of slices—thick, generous slices—of bread dipped in soy and brown sugar, and then fried or toasted. Each slice has a skewer passed63 through it, which the buyer returns after demolishing the bread.

Flour is now used in many other ways besides the manufacture of simple bread. There is Kash-pau, cake bread, which is sold everywhere. As the name implies, it is a sort of sweet breadstuff made into cakes of various sizes and artistic figures, according to the skill and fancy of the baker. To an European palate this Kash-pau is rather dry and tasteless, but it is very cheap, and for five sen (three-halfpence) a huge paper bagful can be bought. Kasuteira, or sponge cake, is not so much sought after as it used to be. Yet some bakeries, such as the Fugetsu-do and Tsuboya, excel in producing the lightest and most delicious sponge cake.

Millet, in China, is only used as food by the very poor.

Wheat is not the primary article of food among the natives of India, and hitherto only enough has been produced for home consumption; but of late years much has been grown for export, and being of a particularly hard nature is useful for mixing with the softer kinds. Still, it is used by itself, and is made into unleavened cakes called Chupatees. These are made by mixing flour and water together, with a little salt, into a paste or dough, kneading it well; sometimes ghee (clarified butter) is added. They may also be made with milk instead of water. They are flattened into thin cakes with the hand, smeared with a small quantity of ghee, and baked on an iron pan, or sheet of iron, over the fire.

Historic, too, is the Chupatee, for by its means the64 message was sent round throughout the length and breadth of British India for the rising against the English rule—known as the Indian Mutiny. Its true meaning was not at first understood, as we may read in the Indian correspondence of the Times, dated Bombay, March 3, 1857: ‘From Cawnpore to Allahabad, and onwards towards the great cities of the North-West, the chokedars, or policemen, have been of late spreading from village to village—at whose command, or for what object, they themselves, it is said, are ignorant—little plain cakes of wheaten flour. The number of cakes, and the mode of their transmission, is uniform. Chokedar of village A enters village B, and, addressing its chokedar, commits to his charge two cakes, with directions to have other two similar to them prepared; and, leaving the old in his own village, to hie with the new to village C, and so on. English authorities of the districts through which these edibles passed looked at, handled, and probably tasted them; and finding them, upon the evidence of all their senses, harmless, reported accordingly to the Government. And it appears, I think, with tolerable clearness, that the mysterious mission is not of political but of superstitious origin; and is directed simply to the warding off of diseases, such as the choleraic visitation of twelve months ago, in which point of view it is noteworthy and characteristic, and not unworthy to be remembered together with last year’s grim and picturesque legend of the horseman, who rode down to the river at dead of night and was ferried across, announcing that the pestilence was in his train.’

65

Apropos of Indian flour, Col. Meadows Taylor, in The Story of My Life, tells a story anent the adulteration of flour in India.

‘During that day my tent was beset by hundreds of pilgrims and travellers, crying loudly for justice against the flour-sellers, who not only gave short weight in flour, but adulterated it so distressingly with sand that the cakes made with it were uneatable, and had to be thrown away. That evening I told some reliable men of my escort to go quietly into the bazaars and each buy flour at a separate shop, being careful to note whose shop it was.

‘The flour was brought to me. I tested every sample, and found it full of sand as I passed it under my teeth. I then desired that all the persons named in my list should be sent to me with their baskets of flour, their weights and scales. Shortly afterwards they arrived, evidently suspecting nothing, and were placed in a row seated on the grass before my tent.

‘“Now,” said I gravely, “each of you is to weigh out a ser (two pounds) of your flour,” which was done. “Is it for the pilgrims?” asked one.

‘“No,” said I quietly, though I had much difficulty to keep my countenance. “You must eat it yourselves.”

‘They saw that I was in earnest, and offered to pay any fine that I imposed.

‘“Not so,” I returned, “you have made many eat your flour; why should you object to eat it yourselves?”

‘They were horribly frightened, and, amid the jeers and screams of laughter of the bystanders, some of them actually began to eat, spluttering out the66 half-moistened flour, which could be heard crunching between their teeth. At last some of them flung themselves on their faces, abjectly beseeching pardon.

‘“Swear!” I cried, “swear by the Holy Mother in yonder temple that you will not fill the mouths of her worshippers with dirt! You have brought this on yourselves, and there is not a man in all the country who will not laugh at the bunnais (flour-sellers) who could not eat their own flour because it broke their teeth.”

‘So this episode terminated, and I heard no more complaints of bad flour.’

The Indian flour mill is very primitive, consisting of two great mill-stones, of which the lower is fast, and the upper is usually turned by two women, who feed the wheat by handfuls into a hole which passes through the stone. The meal so obtained is simply mixed with palm yeast, and baked in very hot ovens, which have been heated for several days. The small European householder finds it more convenient to patronise the Mohammedan bakers, of whom, however, the bread has to be ordered in advance. Sometimes two or three English families combine, and hire a baker, paying him a monthly salary, and providing him with the raw material.

The yeast mentioned above is made from the sap of the date palm. In April, before the flowers appear, a Hindoo climbs the naked trunk—for the leaves, as in all palm trees, are borne on the top. The man’s feet are bound together by a rope, and about his hips are fastened two pots for the reception of the sap. 67As he climbs, he calls out, ‘Darpor, darpor ata hain,’ which, being interpreted, means, ‘The palm-tapper is coming.’ This is for the benefit of the Mohammedan women who might be sitting unveiled in the courtyards of the houses exposed to the view of the climber after he has risen above the tops of the walls. A tapper who once fails to give this warning cry is thenceforth forbidden to ply his trade. When the tapper has reached the crown of the tree he cuts two gashes in opposite sides of the trunk with an axe, which he has carried up in his mouth. Then he fastens the pots under the gashes and descends. The full pots are taken away and empty ones put in their place twice daily. The sap has a sweet taste, and contains some alcohol even when fresh. After standing in the sun in great earthen pots for a few days it begins to ferment, after which it deposits a thick white substance. This, taken at the proper time, is used as yeast.

But rice is, in India, the staff of life, being used to a greater extent than any grain in Europe. It is, in fact, the food of the highest and the lowest, the principal harvest of every climate. Its production, generally speaking, is only limited by the means of irrigation, which is essential to its growth. The ground is prepared in March and April; the seed is sown in May and reaped in August. If circumstances are favourable there are other harvests, one between July and November, another between January and April. These also sometimes consist of rice, but more commonly of other grain or pulse. In some parts millet is used as food. Many are the ways of cooking rice—there are powder of cucumber seeds and68 rice, lime juice and rice, orange juice and rice, jack fruit and rice, rice and milk, and sweet cakes made of rice flour, with or without green ginger.

The Bombay baker is a man of a different stamp altogether to the Bengal baker. He is invariably a Goanese and a native Christian, and adopts his profession not from choice but by heredity. For generations past his fathers have been bakers, and have, in accordance with the rules of the Society of Bakers, to which they must have belonged, studied some portion at least of the art of manufacturing bread. The Bombay baker is, moreover, a man of substance. To begin with, he grows his own wheat, and has it conveyed to his factories, where as many as 200 hands are employed in converting it into raw material for cooking. He retains a staff of chefs, who also hail from Goa, and who attend exclusively to the baking. Greater comparative intelligence and a love for his trade enable him to turn out a far superior article to that of his ignorant contemporary in Upper India; but even in Bombay the same fault has to be found with the manufacturer: either the bread is too fine, or it is too ‘brown’—that is, it contains too much bran.