He tells us that the farther North you go the less wheat is grown, but there is more towards the South, the Swedes having plenty of wheat but more rye. ‘But the Goths, both East and West, who feed on barley and oats, have an infinite abundance given them by70 the mercy of God. Yet there is use made of all these sorts of corn in both places. But the Swedes provide most of rye, where their women know so well how to winnow rye, that for colour, taste, and for health it surpasses the goodness of wheat.’

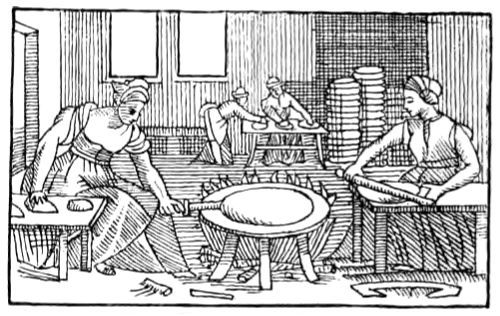

Early Scandinavian Bakeries.

In order to preserve their corn they carefully dried it. ‘On the hottest days, when the sun shines strong, they spread cloths like ships’ sails, or else the sails themselves, upon the ground, or on the tops of mountains where there is no grass, and they lay the corn out to dry for six, or more, or fewer days, as the sun shines hot; then when it is cleaned they lay it up in vessels of oak, or else they grind it, and so lay it up safe, and when it is so dried it will last good for years. But if it be not ground meal, but corn, it is convenient once a year to set it in the sun to be again dried, and thus new-dried corn may be mingled with71 it prudently. But the meal thrust into the oaken vessels, or tuns, by strong ramming it in with wooden mallets, and laid up in a dry place, will last many years, and never be worm-eaten.’

He also discourses on the variety of mills for grinding corn in use. How there was the windmill, that turned by running water, by horse-power, by hands and feet—backwards and forwards, like the pre-historic mealing stones, and also the quern; but he mostly extols the windmills of Holland.

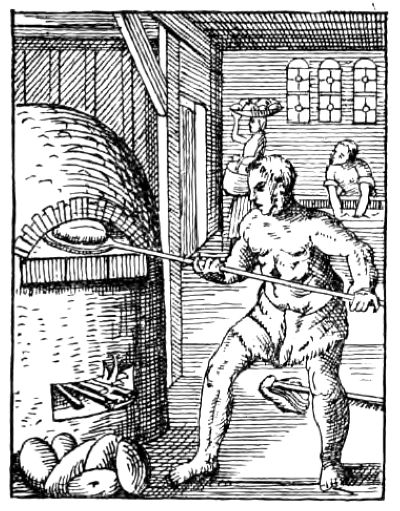

The grain being ground, it was ready for making into bread, and he minutely describes the operation—how it was kneaded into a round shape, then rolled very thin, and finally baked on a sheet of iron, like a warrior’s shield, supported by a tripod, and heated by a slow fire—in fact, the griddle, or girdle, cakes of North Britain. But there was other bread72 which was baked in an oven; and here the artist seems to have drawn somewhat upon his imagination for his cockroaches and blackbeetles. It seems that bread was not sold by weight, and that they were in the habit, about Christmas time, of making what we should call dough babies, about the size of a five-year-old child, of which they made presents, and similar, but smaller, babies of wheat-flour, which they sold.

They also made a gingerbread of flour, honey, and spices, which travellers in the winter made use of; another bread of flour, milk, butter, eggs, and ginger. Then, also, they baked biscuits for shipboard and for victualling forts, but he pathetically points out that these biscuits, if kept for a length of time, especially in a damp place, developed dangerous energy in the shape of weevils, which were harmless (non tamen noxii). He says of the griddle cakes that they would keep good for twenty or more years, by which time they would be reasonably stale.

Scarcely two centuries have passed since rye flour, by itself, or mixed with wheat, furnished nearly all the bread consumed by the labouring classes of England. With the exception of wheat, rye contains a greater proportion of gluten than any other cereal, to which fact it owes its capability of being converted into a spongy bread; and if anyone wishes to try it for themselves, here is a recipe for making Grislex Surbr?d or Husholdinngsbr?d (bread for the household), which is the ordinary bread for the eastern parts of Norway.

73

‘Contrary to our expectations we found white bread everywhere, but the common bread is a heavy bread, the chief ingredient of which is rye. It is always sour—the goodwife intends it to be so. They also have “flat bread” (flad br?d) made of potatoes and rye. It was this kind of bread that the two women whom we happened in upon were making. They were in a little underground room, unlighted except from the door.

‘The women making the bread were seated on either side of a long, low table, upon which were huge mounds of dough. The one nearest the door cut off a piece of this, and moulded it, and rolled it out to a certain degree of thinness; then the other one took it, and, with the greatest care, rolled it still more. At her right hand was the fireplace, and upon the coal was a red piece of iron, forming a huge griddle more than half a yard across. The bread matched this very nearly in size when it was ready to be baked, and it was spread out and turned upon the griddle with great dexterity, and as soon as it was baked it was added to a great heap on the floor.

‘The woman said she should continue to bake bread for thirty days. She had a large family of men who consumed a great deal, and they had to bake very often in consequence. In many places they do not bake bread oftener than twice a year, then it is a circumstance like haying or harvesting. We heard an Englishman say of this bread of the country: “One might eat an acre of it and then not be satisfied.”’

In Denmark, too, rye bread is the rule among the74 peasantry and small farmers—wheaten bread being to them a luxury, and used as cake is with us. In Russia, although its chief export is wheat from the Black Sea, and oats and rye from the Baltic, the peasant eats but rye bread dipped in hemp oil, and even then, as but a few years since, famine visits this granary, and the hapless peasants being reduced to mix orach and bark with their wretched bread, have at times been unable to procure even this, and have died in thousands of starvation. Although Austria-Hungary produces wheat which makes the finest bread-flour in the world, yet throughout the Austrian Empire the peasantry eat rye bread, whilst at Vienna the wheaten bread, especially the Kaiser semmel, which is what we should term a dinner roll or manchet, is simply perfection.

The excellence of the Viennese bread is said to be owing to the bakers, the ovens, and the yeast. The men work according to the traditions of the past, which have been handed down to them. The ovens are heated by wood fires lit inside them during four hours; the ashes are then raked out, and the oven is carefully wiped with wisps of damp straw. On the vapour thus generated, as well as that produced by the baking of the dough, lies the whole art of the browning and the success of the semmel. An ounce of yeast (three decagrammes) and as much salt is taken for every gallon of milk used for the dough. The yeast is a Viennese speciality, known as St. Marxner Pressheffe, and its composition is a secret. It keeps two days in summer and a little longer in winter.

Viennese bread is noted for the fantastic shapes75 into which it is made, but concerning the crescent shape the following legend is told: ‘Many years ago, when there was war between the Austrians and the Turks, the city of Vienna was besieged, and so closely invested that famine seemed inevitable unless the inhabitants yielded and surrendered to the hated Turks. One day a baker in his cellar noticed a peculiar noise, and, looking about, discovered that a boy’s drum on the ground in a corner had some marbles on the parchment, which every little while danced about and caused the odd sound. Surprised, he listened intently, and found that the noise was repeated at regular intervals. He put his ear to the ground and could distinguish a thumping sound, which, on reflection, he concluded must be produced by the enemy undermining the city. He went to the authorities with his story, but at first it was discredited. At last the general in command made an investigation, and found the baker’s suspicions correct. A counter-mine was made and exploded, and the Turks repulsed.

On the restoration of peace, the Emperor of Austria sent for the baker, and expressing his gratitude to him for having saved the city, asked what reward he could claim. The modest baker refused riches or rank, but only asked the privilege of making his bread hereafter in the form of the crescent, which had so long been their terror, so that it might be a reminder to those who ate it that the God of the Christian is greater than the God of the Infidel. So the Imperial order was issued granting the baker and his descendants the sole right76 to make their bread in the shape of the Turkish crescent.’

As in Austria, so in Germany. Good wheaten bread can be got in towns and cities, though not so fine as in Austria, by reason of the flour, and the peasantry are content to have rye and barley bread. Pumpernickel, to wit, is one of the oldest varieties of bread, and the first to come into general use. It is made of barley, and must be baked in an oven especially made for the purpose. This kind of bread is considered very nutritious, and is of a sweet taste. In many parts of Germany there are large bakeries where pumpernickel is baked as a speciality, whence it is sent into the smaller towns, and even exported to other countries in loaves of 4 lbs., 8 lbs., and 12 lbs. weight. At Soest, Unna, and Brostadt large quantities are made for exportation, for the expatriated German carries his love of Fatherland with him, and at Berlin there is also a bakery for making pumpernickel.

The Gauls reaped their wheat, and then threshed it out by means of oxen and horses; but they also cut off the ears, and then reaped the straw. To gather in the panic and millet, they held the stalks by means of a kind of comb, and then cut off the heads with shears. To prevent its being stolen, the corn was hidden in underground storehouses, and often in natural caves, which were afterwards walled up. They used mealing stones, as before described, in order to crush and roughly grind their grain, which was made into an unleavened cake, dry and thin, which was not cut, but was broken when served. They also had a kind of bread called ‘plate bread,’ which they ate soaked77 with sauce or meat gravy. The Gauls made beer from barley, and used it instead of water to mix their dough with. Thus, unconsciously, they discovered the secret of leavened bread; and, by-and-by, noticing that the beer if let alone frothed, and that when used for bread-making in this state the bread was lighter, they left off using the beer, and only employed the yeast.

Barley they called gru, which, in Latin, became grudum. Gruellum was husked barley, which the Gauls ate in soup and with boiled meat. This is the origin of the French word gruau (groats), which is equally applied to husked oats. Rye was used in the northern part of Gaul; and, from the time of Strabo, millet was in use among the Gauls as well as panic, but especially in Aquitaine. They also certainly knew of buck-wheat, which had been cultivated from time immemorial in Africa, for it has been found in several Celtic remains in the Camp de Chalons.

The Romans brought millstones with them, and introduced the water-wheel, which saved them the exertion of personally grinding their corn, and with the arrival of the Franks came Christianity, and they were taught the prayer, ‘Our Father, which art in Heaven ... give us this day our daily bread.’

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries in France, noblemen, the middle-class, and shopkeepers did not eat much white bread, and their best was equal to the ‘household bread’ of to-day, whilst whitey-brown, brown, and bran breads were to be found on their tables. The common folk fed on bread made of78 barley, rye, maslin, a mixture of wheat and rye, brown bread, black bread, and enormous pasties, of which the thick crust was composed of rye, bran, and flour mixed together.

Maize was introduced into France from America in 1560. Champier speaks of it as a plant recently imported, and says: ‘Some poor people, in default of corn, have made bread of it, especially in the Beaujolais, but it is less fitted for men than for animals, which fatten quickly upon it, and especially for pigeons who love it much.’

Vermicelli, macaroni, lazagnes (riband vermicelli) and other Italian pastas were brought into France during the wars of Charles VIII., and had no other rivals than rice.

At this time, in making bread, the yeast of beer was partially abandoned, and other ferments were made use of. The Flemings boiled wheat, and, after having skimmed off the froth, used it as a leaven, which gave them a bread much lighter than hitherto, or, according to Champier and Liébaut, who wrote in 1589, they employed vinegar, wine, and rennet; and from their writings we find that the farmers were their own millers and bakers.

‘It would be useless for the labourer to take so much pains with his land, if he only derived a profit from a sale of the grain which he has harvested, if he could not himself make cakes, flammèches (flaky pastry), flans (cakes made with flour, eggs, milk and butter), fritters, and a thousand other dainties, which he can make with a flour from his own corn; and it would be very unbecoming in him were he to borrow79 them from his neighbours, or buy them of the bakers or pastrycooks.

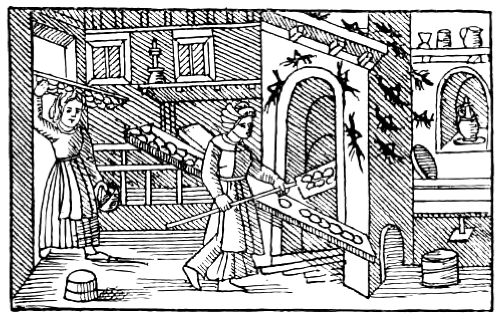

A Medi?val Bakery.

(From an engraving by Jost Amman.)

‘The farmer’s duty is to choose his corn, have it ground, and to keep the flour in the granary, whence he will soon take it in order to make bread. The handling of the flour and kneading the dough is entirely the care of the wife, who ought to give all her best energies to it, for of all food bread is the best; one gets tired of the most delicate meats, but never of bread.’

From this time till the present there is no great80 story to tell of bread in France. It has progressed in quality, as in every other country, until French bread is famous throughout the civilised world. But this is mainly in the towns; black bread is still in use in some of the rural parts of France, and one can imagine the relish with which the peasant tastes once more the bread of his youth after having been deprived of it for some time.

In Paris, at one time, the monks controlled the bakery business; they had the monopoly of the public ovens, where housewives brought the dough to be baked, just as nowadays they take a shoulder of mutton and potatoes. But no baking was allowed on Sundays and fête days. France thus observed Sunday as a whole holiday, and the oven-tax went towards the support and burial of the poor. Up to 1789 the bakers were compelled to sell nearly all their bread at stalls in the public markets, and 900 master bakers monopolised the privilege; for it was only in 1863 that the trade became free and thrown open to all. Previous to that, in order to qualify for a master baker, it was necessary to graduate five years as an apprentice, and four more as a journeyman; also the sale of fancy bread was obliged to be carried on in an underhand way, and it was delivered in secret, being subject to a tax, and the baker not being able to make it of exact weight, without prejudice, on account of its great extent of crust.

American flour is celebrated all over the world, and is more extensively used in England, especially the finest sorts for pastry; but, of course, the demand for it in the immense continent itself is something81 enormous. Take one instance, Philadelphia, which is celebrated for its good bread. Over one million barrels are sold in that city annually for home consumption, and two-thirds of this is made into bread. The 1300 bakers in Philadelphia use 600,000 barrels, a barrel of good flour making from 270 to 280 five cent. loaves, and the best flour is the cheapest to use. As a rule, the bakers use choice brands, and mix four grades to get the proper alloy, so to speak—two ‘Minnesota springs’ and two ‘Indiana winters.’ Some bakers, especially those who make the best breads, use only one grade of spring wheat and two of winter. In the olden time yeast was made of malt, potatoes, and hops, and it is still largely used, but the bakers of fancy breads use a patent yellow compressed yeast. There are seven large steam bread bakeries in Philadelphia, giving employment to three or four hundred hands. One large establishment manufactures the different varieties of Vienna bread exclusively. It is made of the best flour, and milk instead of water is used to mix the flour. The baking is done in air-tight ovens, and the steam generated in baking settles back on the bread instead of escaping. This makes the outer crust thin and tender, and gives the bread a particularly rich taste and pleasant aroma.

With the addition of maize and buckwheat, the Americans use the same cereals for making bread as we do; but, of course, as is the case with every nation, there are specialities which do not travel abroad. Graham bread is our wholemeal bread, and should be made with the unbolted meal of wheat, and82 not only that, but the wheat of which it is made should be good plump grain, otherwise there would be a disproportionate quantity of bran.

Then there is Boston brown bread, for which the following is the formula: One quart Indian corn meal, one quart Graham, one quart rye flour, one quart white flour, one quart boiling water, one pint yeast, one small cup of molasses, two teaspoonfuls of salt, half-cup of burnt sugar colouring. For rye and Indian corn bread it is only necessary to change the above recipe by leaving out the Graham and white flour and doubling the proportions of Indian corn meal and rye in their place.

Of rolls there are very many varieties besides the ordinary French rolls. Many hotels have their speciality in this class of bread, and, consequently, we have Parker, Tremont, Revere, Brunswick, Clarendon, St. James, Windsor, &c., rolls, besides which there are twist and sandwich rolls.

Early Scandinavian Bakeries.