Diodorus Siculus, who lived just before the Christian era, must have taken his account of the Britons from Pytheas. In Book V., c. 2, he says: ‘They dwell in mean cottages, covered for the most part with reeds and sticks. In reaping their corn, they cut the ears from off the stalk, and house them in repositories under ground; thence they take and pluck out the grains of as many of the oldest of them as may serve them for the day, and, after they have bruised the corn, make it into bread,’

It is said, also, that about this time the Britons exported corn to Gaul and also up the Rhine. On C?sar’s arrival he found them an agricultural people, with abundance of wheat and barley; and during the time of the Roman occupation they made great advances in agriculture. After their departure a hide84 of land was 180 acres if it was cultivated on the Roman three-field system, or 160 if on the English plan of two-field course. In the former, one portion was sown with winter wheat, a second with spring wheat, whilst the third lay fallow. The English way was to divide the hide, and in each half to sow alternately spring and winter wheat, and the chief crops raised were rye, oats, barley, wheat, beans and peas. In social rank, the yeoman, or geneat (tenant farmer), ranked next after the thegn and the priest, whilst even the baker was an important member of a thegn’s household—the bread being made in round flat cakes from wholemeal (for there is no mention of bolting it), ground in a hand-mill or quern. Such were doubtless the storied cakes which Alfred watched for the neatherd’s wife.

The peasants’ bread was principally made of rye, oats, and beans, the wheat being used by the ‘gentry’ only—ordinary bread being made of barley; and, connected with the latter, are derived our names of Lord and Lady, the first from Llaford, originator of bread, or bread-ward, the latter from Ll?fdige, bread-maid, or bread-maker. So, too, we owe our wedding cake to the great loaf made by the bride to show her inauguration into housewifery, which was partaken of by the wedding guests.

The peasant baked his bread on iron plates or in rude ovens, and ground his coarse meal in hand-mills; but in later times water was made the principal motive power for grinding corn, and about 5000 mills are mentioned in Domesday Book; but they are not particularised as to what power they were worked by.

85

As a trade, the bakers of London rank from a very early date. They formed a brotherhood, or guild, in the reign of Henry II., about 1155. Stow says of them: ‘The Company of White Bakers are of great antiquity, as appeareth by their Records, and divers other things of antiquity, extant in their Common Hall. They were a Company of this City in the first year of Edward II., and had a new Charter granted unto them in the first year of Henry VII., the which Charter was confirmed unto them by Henry VIII., Edward VI., Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth, and King James I. Their Arms were anciently borne; the crest and supporters were granted to them by Robert Cook, Clarencieux, the Letters Patent bearing date November 8 (32 Eliz.), 1590. The Cloud on the Chief thro’ which the Hand holding the Scales Cometh, hath a Glory, omitted in the edition printed 1633; and on each side of the Hand are two Anchors, here also omitted; as by the Visitation Book, Anno 1634, appears.’

Stow describes the Company of the Brown Bakers as ‘A Society of long standing and continuance, prevailed to have their Incorporating granted the ninth day of June, in the 19th year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James I.’

The Arms of both White and Brown Bakers are copied from Harl. MSS. 1464, 57e. (73), A.D. 1634—the Arms of these and other Companies being copied from the Herald’s Visitation of that year, by Rd. Price, Armes-Painter.

The Arms of the White Bakers.

Heraldically described, the Arms of the White Bakers are—Gules, three Garbs Or, a chief barry86 wavy of four, argent and azure, an arm issuing from clouds radiated of the second, the hand holding a pair of scales depending between the upper Garbs, also of the second. Crest: Two Arms embowed issuing out of clouds, proper, holding in the hands a chaplet of wheat, or. Supporters: Two Stags, proper,87 attired, or, each gorged with a chaplet of wheat, of the last.

The Arms of the Brown Bakers closely resemble those of their white brethren, but are not so dignified, as lacking supporters and motto: Vert, a chevron quarterly, or and gules, charged with a pair of88 balances, azure, holden by a hand out of a cloud, proper, between three garbs of beans, rye and wheat, or. On a chief barry of five, wavy, argent and azure, an Anchor couchant, or. Crest: An Arm quarterly of the second, the hand holding a bean sheaf, proper.

W. Carew Hazlitt, in his Livery Companies of the City of London (Lond. 1892) says: ‘In the Elizabeth, as in the Henry VIII. Charter, the White Bakers had taken the initiative in drawing the makers of brown bread, whose business was far more limited and unimportant, into union with them on unequal terms, and the latter body dissented and renounced; whereupon the Queen was advised by the Lords of the Council to recall her patent. This proceeding seems, for a time, to have caused the matter to drop; but in 19 James I., June 6, 1622, the Brown Bakers succeeded in securing separate incorporation, with a common seal, a Master, three Wardens, and sixteen Assistants, as well as all other usual rights and powers. We hear nothing further of the matter till 1629, when the two bodies were still separate, the White Bakers being assessed for a levy by the City in that year at £25 16s., the other at £4. 6s., a proof of the relative weight and resources of the disputants, which is confirmed by the proportions contributed by each to the Ulster scheme a few years prior, namely, £480 and £90. In 1654 the Brown Bakers had apparently relinquished their independent quarters at Founders’ Hall, Lothbury, as if an union had been arranged; and in 2 James II. the charter was received with the usual restrictions in regard to the oaths of allegiance and supremacy, and conformity to the Church of89 England, but otherwise in such a form as to lead to the belief that it comprehended both sections of the trade.’

The Bakers’ Company ranks very high after the twelve great City Companies, on account of its great antiquity. Its Hall, in Stow’s time, was in ‘Hart Lane, or Harp Lane, which likewise runneth (from Tower Street) into Thames Street. In this Hart Lane is the Bakers’ Hall, some time the dwelling-house of John Chichley, Chamberlain of London.’ And in Harp Lane it still is. According to Whitaker’s Almanack for 1904 its livery numbers 152 and its total income is only £1900.

Much early legislation was passed regarding bakers and their calling, but, in spite of it all, some bakers did not amend their ways, and an amusing grievance was made by Fabyan as to their punishment. In his Chronicles, under date of 1268, and speaking of the harshness of Sir Hugh Bigod, justice, he says: ‘In processe of tyme after, the sayde syr Hughe, wt. other, came to Guylde hall, and kepte his courte and plees there withoute all ordre of lawe, and contrarye to the lybertyes of the cytie, and there punysshed the bakers for lacke of syze, by the tumberell, where before tymes they were punysshed by the pyllery, and orderynge many thynges at his wyll, more than by any good ordre of lawe.’ And Holinshed repeats the story.

Nor were their misdeeds confined to their trade, as we may learn from the Archives of the City of London. In fact, their evil deeds were so notorious that the King himself had to take cognizance of them.

90

That the bakers wanted looking after is well evidenced by the following extracts from the City archives:

26 Edward I., A.D. 1298. ‘Be it remembered that on Wednesday next after the Feast of St. Lawrence (August 10), in the 26th year of the reign of King Edward, Juliana, la Pestour of Neutone (the baker of Newington), brought a cart laden with six shillings’ worth of bread into West Chepe; of which bread, that which was light bread was wanting in weight, according to the assise of the halfpenny loaf, to the amount of 25 shillings in weight. [The shilling of silver being three-fifths of an ounce in weight, this deficiency would be 15 ounces.] And of the said six shillings’ worth, three shillings’ worth was brown bread; which brown bread was of the right assise. It was, therefore, adjudged that the same should be delivered to the aforesaid Juliana, by Henry le Galeys, Mayor of London, Thomas Romeyn, and other Aldermen. And the other three shillings’ worth, by award of the said Mayor and Aldermen, was ordered to be given to the prisoners in Newgate.’

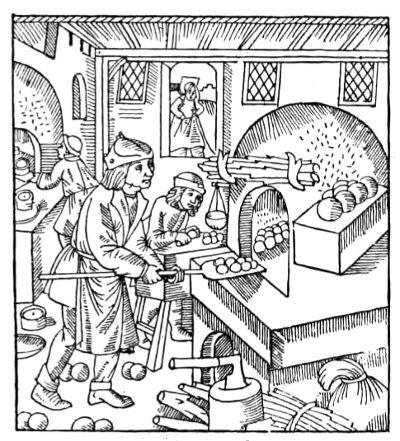

An Early Bakery.

3. Edward II., A.D. 1310. ‘On the Monday next before the Feast of St Hilary (13th January), in the third year of the reign of Edward, the son of King Edward, the bread of Sarra Foting, Christina Terrice, Godiyeva Foting, Matilda de Bolingtone, Christina Pricket, Isabella Sperling, Alice Pegges, Joanna de Cauntebrigge, and Isabella Pouvestre, bakeresses of Stratford [The bread of London, in these times, was extensively made in the villages of Bromley (Bremble), Middlesex, and Stratford-le-Bow.] Stow91 says, ‘And because I have here before spoken of the bread carts coming from Stratford at the Bow, ye shall understand that of old time the bakers of bread at Stratford were allowed to bring daily (except the Sabbath and principal feasts) divers long carts laden with bread, the same being two ounces in the penny wheat loaf heavier than the penny wheat loaf baked in the City, the same to be sold in Cheape, three or four carts standing there, between Gatheron’s Lane92 and Fauster’s Lane end, one cart on Cornhill, by the Conduit, and one other in Grasse Street. And I have read that in the fourth year of Edward II., Richard Reffeham being Mayor, a baker named John, of Stratforde, for making bread less than the assise, was, with a fool’s hood on his head and loaves of bread about his neck, drawn on a hurdle through the streets of the City. Moreover, in the 44th of Edward III., John Chichester being Mayor of London, I read in the Visions of Piers Plowman, a book so called, as followeth:

At Londone I leve,

Liketh wel my waires;

And louren whan thei lakken hem.

It is noght long y passed,

There was a careful commune,

Whan no cart came to towne

With breed fro Stratforde:

Tho gennen beggaris wepe,

And werkmen were agast a lite;

This wole be thought longe.

In the date of oure Drighte,

In a drye Aprill.

A thousand and thre hundred

Twies twenty and ten,

My waires were gesene

Whan Chichestre was Maire.’]

was taken by Roger le Paumer, Sheriff of London, and weighed before the Mayor and Aldermen; and it was found that the halfpenny loaf weighed less than it ought by eight shillings. But, seeing that the bread was cold, and ought not to have been weighed in such state, by the custom of the City, it was agreed that it should not be forfeited this time. But,93 in order that such an offence as this might not pass unpunished, it was awarded as to bread so taken that three halfpenny loaves should always be sold for a penny, but that the bakeresses aforesaid should this time have such penny.’

5. Edward II., A.D. 1311. ‘The bread taken from William de Somersete, baker, on the Thursday next before the Feast of St. Laurence (10th August) in the fifth year of the reign of King Edward, was examined and adjudged upon befor Richer de Refham, Mayor, Thomas Romayn, John de Wengrave, and other Aldermen; and, because it was found that such bread was putrid, and altogether rotten, and made of putrid wheat, so that persons by eating that bread would be poisoned and choked, the Sheriff was ordered to take him, and have him here on the Friday next after the Feast of St. Laurence; then to receive judgment for the same.’

In the 1 Ed. III. (1327) a curious fraud was brought to light, and John Brid and seven other bakers, and two bakeresses, were tried before the Mayor and Aldermen, ‘for that the said John, for falsely and maliciously obtaining his own private advantage, did skilfully and artfully cause a certain hole to be made upon a table of his, called a molding borde pertaining to his bakehouse, after the manner of a mouse-trap, in which mice are caught, there being a certain wicket warily provided for closing and opening such hole.

‘And when his neighbours and others, who were wont to bake their bread at his oven, came with their dough, or material for making bread, the said John94 used to put the said dough or other material upon the said table, called a molding borde, as aforesaid, and over the hole before mentioned, for the purpose of making loaves therefrom for baking; and such dough or material being so placed upon the table aforesaid, the same John had one of his household, ready provided for the same, sitting in secret beneath such table; which servant of his, so seated beneath the hole, and carefully opening it, piecemeal, and bit by bit, craftily withdrew some of the dough aforesaid, frequently collecting great quantities of such dough, falsely, wickedly, and maliciously, to the great loss of all his neighbours and persons living near, and of others who had come to him with such dough to bake, and to the scandal and disgrace of the whole City, and, in especial, of the Mayor and Bailiffs for the safe keeping of the assizes of the City assigned. Which hole, so found in his table, aforesaid, was made of aforethought; and, in like manner, a great quantity of such dough that had been drawn through the said hole was found beneath the hole, and was, by William de Hertynge, serjeant-at-mace, and Thomas de Morle, clerk of Richard de Rothynge, one of the Sheriffs of the City aforesaid, who had found such material, or dough, in the suspected place before mentioned, upon oath brought here into Court.’

All the prisoners pleaded Not Guilty; but the case was too clear against them, and ‘It was agreed, and ordained, that all those of the bakers aforesaid, beneath whose tables with holes dough had been found, should be put upon the pillory, with a certain95 quantity of such dough hung from their necks; and that those bakers in whose houses dough was not found beneath the tables aforesaid, should be put upon the pillory, but without dough hung from their necks; and that they should so remain upon the pillory until Vespers at St. Paul’s in London should be ended.’ The women were committed to Newgate.

There was another punishment by which bakers, in common with all who told lies, or libelled, or scandalised their neighbour, had to stand in the pillory with a whetstone hung round their neck.

England suffered much from dearth. Holinshed tells us how, in 1149, ‘The great raine that fell in the summer season did much hurt unto corne standing on the ground, so that a great dearth followed. 1175.—The same yeare both England and the countries adjoining were sore vexed with great mortalitie of people, and immediatlie after followed a sore dearth and famine. 1196.—Here is also to be noted, that in this seventh yeare of King Richard, chanced a dearth through this realme of England, and in the coasts about the same. 1199.—Furthermore I find that in the daies of this King Richard a great dearth reigned in England, and also in France, for the space of three or foure yeares during the wars betweene him and King Philip, so that, after his returne out of Germaine, and from imprisonment, a quarter of wheat was sold at eighteen shillings eight pence, no small price in those daies, if you consider the alay of monie then currant.

‘1222.—Likewise on the day of the exaltation of the Crosse, a generall thunder happened through96out the realme, and thereupon followed a continuall season of foule weather and wet, till Candlemas next after, which caused a dearth of corne, so as wheat was sold at twelve shillings the quarter.

‘1245.—Again the King, of purpose, had consumed all the provision of corne and vittels which remained in the marshes, so that in Cheshire, and other parts adjoining, there was such dearth that the people scarse could get sufficient vittels to susteine themselves withall.

‘1258.—In this yeare was an exceeding great dearth, insomuch that a quarter of wheat was sold at London for foure and twentie shillings, whereas within two or three yeares before, a quarter was sold at two shillings. It had been more dearer, if great store had not come out of Almaine; for in France and in Normandie it also failed. But there came fiftie great ships fraught with wheat and barlie, with meale and bread out of Dutch land, by the procurement of Richard, King of Almaine, which greatlie releeved the poore; for proclamation was made, and order taken by the King, that none of the citizens of London should buy anie of that graine to laie it up in store, whereby it might be sold at an higher price unto the needie. But, though this provision did much ease, yet the want was great over all the realme. For it was certainlie affirmed that in three shires within the realme there was not found so much graine of that yeare’s growth as came over in those fiftie ships. The proclamation was set forth to restrein the Londoners from ingrossing up that graine, and not without cause; for the wealthie citizens were evill97 spoken of in that season, bicause in time of scarcitie they would either staie such ships as, fraught with vittels, were comming towards the citie, and send them some other way forth, or else buy the whole, that they might sell it by retaile, at their pleasure, to the needie. By means of this great dearth and scarcitie, the common people were constrained to live upon herbs and roots, and a great number of the poore people died through famine. They died so thicke that there were great pits made in churchyards to laie the dead bodies in, one upon another.

‘1289.—There insued such continuall raine, so distempering the ground, that corne waxed verie deare, so that whereas wheat was sold before at three pence a bushell, the market so rose by little and little that it was sold for two shillings a bushell, and so the dearth increased still almost for the space of 40 yeares, till the death of Edward the Second, in so much that sometimes a bushel of wheat, London measure, was sold at ten shillings. 1294.—This yeare in England was a great dearth and scarcity of corne, so that a quarter of wheat in manie places was sold for thirtie shillings; by reason whereof poor people died in manie places for lack of sustnance.

‘1316.—The dearth, by reason of the unseasonable weather in the summer and harvest last past, still increased, for that which with much ado was inned, after, when it came to the proofe, yeelded nothing to the value of that which in sheafe it seemed to conteine, so that wheat and other graine which was at a sore price before, now was inhanced to a farre98 higher rate, the scarcitie thereof being so great that a quarter of wheat was sold for fortie shillings, which was a great price, if we shall consider the allaie of monie then currant. Also, by reason of the murren that fell among cattell, beefes and muttons were unreasonablie priced.... In this season vittles were so scant and deere, and wheat and other graine brought to so high a price, that the poore people were constreined through famine to eat the flesh of horses, dogs, and other vile beasts, which is wonderfull to beleeve, and yet, for default, there died a great multitude of people in divers places of the land. Foure pence in bread of the coarser sort would not suffice one man a daie. Wheat was sold at London for foure marks a quarter and above. Then after this dearth and scarcitie of vittels issued a great death and mortalitie of people; so that what by warres of the Scots, and what by this mortalitie and death, the people of the land were wonderfullie wasted and consumed. O pitifull depopulation!

‘1335.—This yeare there fell great abundance of raine, and thereupon insued morren of beasts; also corne so failed this yeare that a quarter of wheat was sold at fortie shillings. 1353.—In the summer of this season and twentieth yeare, was so great a drought that from the latter end of March fell little raine till the latter end of Julie, by reason whereof manie inconveniences insued; and one thing is specially to be noted, that corne the yeare following waxed scant, and the price began this yeare to be greatlie inhanced. Also beeves and muttons waxed deare for the want of grasse; and this chanced both in England and99 France, so that this was called the deere summer. The Lord William, Duke of Baviere or Bavaria, and Earl of Zelund brought manie ships in London fraught with rie for the releefe of the people, who otherwise had, through their present pinching penurie, if not utterlie perished yet pittifullie pined.

‘1370.—By reason of the great wet and raine that fell this yeare in more abundance than had been accustomed much corne was lost, so that the price thereof was sore inhanced, in so much that wheat was sold at three shillings four pence the bushell. 1389.—Herewith followed a great dearth of corne, so that a bushell of wheat in some places was sold at thirteen pence, which was thought to be a great price. 1394.—In this yeare was a great dearth in all parts of England, and this dearth or scarcitie of corne began under the sickle, and lasted till the feast of Saint Peter ad Vincula—to wit, till the time of new corne. This scarcitie did greatly oppresse the people, and chieflie the commoners of the poorer sort. For a man might see infants and children in streets and houses, through hunger, howling, crieing, and craving bread, whose mothers had it not (God wot) to breake unto them. But yet there was such plentie and abundance of manie years before, that it was thought and spoken of manie housekeepers and husbandmen, that if the seed were not sowen in the ground, which was hoorded up and stored in barnes, lofts, and garners, there would be enough to find and susteine all the people by the space of five years following.... The scarcity of victuals was of greatest force in Leicestershire, and in the middle parts of100 the realme. And although it was a great want, yet was not the price of corne out of reason. For a quarter of wheat, when it was at the highest, was sold at Leicester for 16 shillings 8 pence at one time, and at other times for a market of 14 shillings; at London and other places of the land a quarter of wheat was sold for 10 shillings, or for little more or lesse. For there arrived eleven ships laden with great plentie of victuals at diverse places of the land, for the reliefe of the people. Besides this, the citizens of London laid out two thousand marks to buy food out of the common chest of orphans, and the foure and twentie aldermen, everie of them put in his twentie pounds apeece for necessarie provision, for feare of famine likelie to fall upon the cities. And they laid up their store in sundrie of the fittest and most convenient places they could choose, that the needie and such as were wrong with want might come and buy at a certaine price so much as might suffice them and their families; and they which had not readie monie to paie downe presentlie in hand, their word and credit was taken for a yeare’s space next following, and their turn served. Thus was provision made that people should be relieved, and that none might perish for hunger.

‘1439.—This yeare (by reason of great tempests, raging winds, and raine) there arose such scarsitie that wheat was sold at three shillings foure pence the bushell.... Whereupon Steven Browne, at the same season maior of London, tendering the state of the Citie in this want of bread corne, sent into Pruse certeine ships, which returned laden with101 plentie of rie; wherewith he did much good to the people in that hard time, speciallie to them of the Citie, where the want of corne was not so extreame as in some other places of the land, where the poore distressed people that were hunger-bitten made them bred of ferne roots, and used other hard shifts, till God provided remedie for their penurie by good successe of husbandrie. 1527.—By reason of the great wet that fell in the sowing time of the corne, and in the beginning of the last yeare; now, in the beginning of this, corne so failed, that in the Citie of London, for a while, bread was scant, by reason that the commissioners appointed to see order taken in shires about, ordeined that none should be conveied out of one shire into another. Which order had like to have bred disorder, for that everie countrie and place was not provided alike, and namelie London, that maketh her provision out of other places, felt great inconvenience thereby, till the merchants of the Stillard and others out of the Dutch countries brought such plentie that it was better cheape in London than in anie other part of England, for the King also releeved the citizens in time of their need with a thousand quarters, by waie of lone, of his owne provision.’

By the foregoing we see that the bad dearths came at longer intervals, probably owing to better husbandry, and the regular importation of foreign corn before a scarcity could arise. But, on the other side, I have to chronicle a few (unfortunately only too few) years of exceeding plenty. The first one recorded was in 1288, and is thus recorded by Stow: ‘The102 summer was so exceeding hote this yeere that many men died through heate, and yet wheate was solde at London for three shillings foure pence the quarter when it was dearest, and in other partes abroad the same was sold for twentie pence or sixteen pence the quarter; yea, for twelve pence the quarter, and in the west and north parts for eight pence the quarter; barley for six pence, and oats for foure pence the quarter, and such cheapnesse of beanes and pease as the like had not been heard. 1317.—This yeere was an early harvest, so that all the corne was inned before St Giles day (Sep. 1). A bushel of wheat that was before for X shillings was solde for ten pence; and a bushel of otes that before was eyght shillings was solde for eyght pence.’

Holinshed tells us that in 1493 wheat was sold in London at 6d. the bushel; and in 1557.—‘This yeare, before harvest wheat was sold for foure marks the quarter, malt at foure and fortie shillings the quarter, and pease at six and fortie shillings and eight pence; but, after harvest, wheat was sold for five shillings the quarter, malt at six shillings eight pence, rie at three shillings foure pence. So that the penie wheat loafe that weied in London the last yeere but eleven ounces Troie weied now six and fiftie ounces Troie. In the countrie wheat was sold for foure shillings the quarter, malt at foure shillings eight pence; and, in some places a bushell of rie for a pound of candles, which were foure pence.’

Arms of the Brown Bakers.