As with the water-wheel, so its congener, the windmill, beloved of artists, is going. A motive power as cheap as water is the wind, but, unfortunately, it is not so reliable. It is believed that the Chinese were the first to use the wind as a motive power for mills, and we have no record as to when they were introduced into Europe; we only know they were in use in the twelfth century. As a rule, in England, windmills have four arms, or ‘whips,’ but sometimes they104 have six. These arms are generally covered with strong canvas, but occasionally they are covered with thin boarding; they are set at an angle, which varies according to the fancy of the miller, but the shaft to which they are attached (called the ‘wind shaft’) is invariably placed at an inclination of 10 or 15 degrees, in order that the revolving arms should clear the bottom portion of the mill.

A Post Mill.

A Water-Wheel Mill.

The oldest kind of windmill is called a post mill, 105

106because the whole structure is centred on a post, or pivot, and, when the wind shifts, the mill has to be turned bodily to meet it, by means of a long lever. The smock, or frock, windmill is an improvement upon the post mill; the building itself is stationary and permanent, but the head or cap, where is the wind shaft, rotates, and this is more easily managed.

For hundreds of years people were contented with the four and six arms to their windmills, and it was only in modern times that Messrs. J. Warner and Sons, of Cripplegate, London, patented their annular sails, which, as is plain to the meanest capacity, are vastly superior. The shutters, or ‘vanes,’ are connected with spiral springs, which keep them up to the best angle of ‘weather, for light winds. If the strength of the wind increases, the vanes give to the wind, forcing back the springs, and thus the area on which the wind acts diminishes. In addition, there are a striking lever and tackle for setting the vanes edgeways to the wind, when the mill is stopped, or a storm expected.

We have seen how from the very first man used stones wherewith to triturate his corn, and to this day stones are still used for grinding, although their days are in all probability numbered, and in a very little time they, with the windmill, will be relegated to limbo. The Encyclop?dia Britannica gives such an excellent description of these mill-stones, that I quote it in its entirety.

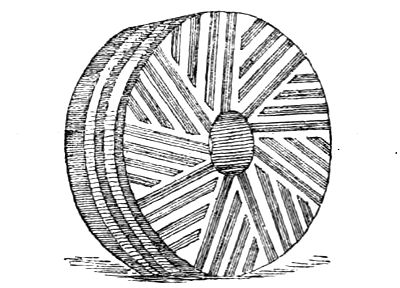

The Grinding Surface of a Millstone.

‘They consist of two flat cylindrical masses inclosed within a wooden or sheet metal case, the lower, or bed-stone, being permanently fixed, while the upper,107 or runner, is accurately pivoted and balanced over it The average size of millstones is about four feet two inches in diameter, by twelve inches in thickness, and they are made of a hard but cellular siliceous stone, called buhr-stone, the best qualities of which are obtained from La-Ferté-sous-Jouarre, department of Seine et Marne, France. Millstones are generally built up of segments, bound together round the circumference by an iron hoop, and backed with plaster of Paris. The bed-stone is dressed to a perfectly flat plane surface, and a series of grooves, or shallow depressions, are cut in it, generally in the manner shown, which represents the grinding surface of an upper or running stone. The grooves on both are made to correspond exactly, so that when the one is rotated over the other the sharp edges of the grooves,108 meeting each other, operate like a rough pair of scissors, and thus the effect of the stones on grain submitted to their action is at once that of cutting, squeezing, and crushing. The dressing and grooving of millstones is generally done by hand picking, but sometimes black amorphous diamonds (carbonado) are used, and emery wheel dressers have likewise been suggested. The upper stone, or runner, is set in motion by a spindle on which it is mounted, which passes up through the centre of the bed-stone, and there are screws and other appliances for adjusting and balancing the stone. Further provision is made within the stone case for passing through air to prevent too high a heat being developed in the grinding operation, and sweepers for conveying the flour to the meal spout are also provided.

‘The ground meal delivered by the spout is carried forward in a conveyor, or creeper box, by means of an Archimedean screw, to the elevators, by which it is lifted to an upper floor to the bolting or flour-dressing machine. The form in which this apparatus was formerly employed consisted of a cylinder mounted on an inclined plane, and covered externally with wire cloth of different degrees of fineness, the finest being at the upper part of the cylinder, where the meal is admitted. Within the cylinder, which was stationary, a circular brush revolved, by which the meal was pressed against the wire cloth, and, at the same time, carried gradually towards the lower extremity, sifting out, as it proceeded, the mill products into different grades of fineness, and finally delivering the coarse bran at the extremity of the109 cylinder. For the operation of bolting or dressing, hexagonal or octagonal cylinders, about three feet in diameter, and from 20 to 25 feet long, are now commonly employed. These are mounted horizontally on a spindle for revolving, and externally they are covered with silk of different degrees of fineness, whence they are called “silks,” or “silk dressers.” Radiating arms or other devices for carrying the meal gradually forward as the apparatus revolved, are fixed within the cylinders; and there is also an arrangement of beaters, which gives the segments of cloth a sharp tap, and thereby facilitates the sifting action of the apparatus. Like all other mill machines, the modifications of the silk dresser are numerous,’

We have seen the ordinary operation of grinding flour in the old-fashioned way; now let us notice the improvements in making wheat into flour.

‘We will suppose that the wheat has arrived by lighter at one of the large mills on the Thames, and that it has been shovelled into sacks and hoisted into the warehouse. The process by which it is turned into flour may be divided into three stages: (1) cleaning, (2) breaking, (3) grinding; but the number and complexity of the operations included in these stages are astounding. It must be understood that the following description refers to a first-class London mill—that is, one which has, certainly no superior, and, probably, no equal, in the world.

‘In the first stage the wheat is merely prepared for the mill, and this is done in the cleaning department, which is separate from the mill proper. From the warehouse the grain is passed to a sifter or “separator,110” which is a kind of sieve. Here the grosser impurities—straw, sticks, stones, earth, seeds, and what not—are removed. Thence to an “elevator,” precisely similar in principle to that previously described, and by the elevator straight to the top of the building. Here it enters a wire sieve in the form of a revolving hexagonal “reel,” by which the smaller heavy impurities with which it is still mixed are separated. Passing through this, it drops into the next storey, to be subjected to the “aspirator,” an apparatus by means of which currents of air are blown through the grain as it falls and carry off the lighter and more volatile rubbish mixed with it. In the next floor is an ingenious instrument with a special purpose. Among the wheat is still a quantity of small black seeds, known as “cockle” seeds, and to get rid of these the “cockle cylinder” is employed. It is a revolving metal cylinder, the inner surface of which is fitted with small holes; the grain passes into the interior of the cylinder, and as the latter goes round and round the cockle seeds stick in the small holes and are carried up to a certain height, when they fall out and are caught by an “apron”; while the wheat, which is too large to stick in the holes, continually falls back into the bottom of the cylinder. Again our corn drops a storey, and encounters the “decorcitator.” The object of this apparatus is to knock off the dust and dirt adhering to the grains, and it is effected by agitating them between two metal surfaces at a high rate of speed. The amount of dust removed by this method from apparently clean grain is astonishing. In the next storey is another decorcitator, and below that111 a second aspirator, which brings us once more to the ground.

‘On reaching the ground floor again, our now clean wheat is first passed through the “grading” or “sizing” reels, which separate it into two sizes, and then it enters the mill proper. It should be said here that the milling industry of the world has been revolutionised within the past few years by the substitution of steel rollers for the old millstones. The process of crushing or grinding, however, by steel rollers is accomplished in a very gradual manner, as will be explained: First come the “break rolls.” These are solid steel rollers set in pairs, with corrugated surfaces; this gives them a cutting action. Wheat is passed through five successive pairs of these rollers. The first are about 1/16th inch apart, and only break or bruise the grain slightly. Each successive pair is set closer, and carries the bruising a step further. But this is only half the business. After each set of rollers the grain goes through a “purifier,” which is either a sieve of some kind or an aspirator, or both together, and the object is always the same—namely, to separate the solid particles of the broken wheat from the lighter ones. The former are, or rather will eventually be, flour; the latter constitute “offal.” And the whole art of milling is merely an extension of this process; first reduction, then separation, repeated over and over again. As the grain passes through each successive set of rollers it is broken up finer and ever finer, and the separating action of the “purifier” accompanies it step by step. The solid particles grow smaller and smaller, the112 “offal” correspondingly finer and finer. This is the process in brief, but there are endless complications and refinements on the way. For instance, the solid particles are not only separated but are themselves divided into groups according to size. Then the offal often undergoes a further purifying process. Then the purifiers differ—some are complex, others simple; some of wire, others of silk; some revolve, others oscillate; some are “aspirated,” others not; and so forth. Meanwhile, at the end of the five rolls and five purifiers, which make up our breaking department, we have got three products: (a) semolina; (b) middlings; (c) offal. The first two are practically varieties of the same—i.e., both solid particles, which will afterwards be flour, but of different sizes. They are half way between grain and flour—hence the term “middlings.”

‘Grinding is only a continuation of the above process, but the rollers are different; their surfaces are smooth, and they are set closer together. The purifiers, too, are, for the most part, more elaborate. A look at one of them will show the extreme ingenuity expended on these operations. It consists primarily of an oscillating sieve made of silk, through the meshes of which the particles of flour fall into a wooden bin. On the floor of the bin is a “worm” which continually works the flour along to one end; on the under surface of the sieve is a travelling brush which brushes off the adhering flour and prevents the meshes from getting clogged. Above the sieve is an apparatus which, with the aid of currents blown by an aspirator, catches the volatile offal; and above113 that again a travelling blanket which arrests the still more volatile particles. Finally, the blanket, as it reaches the end, is tapped automatically to knock out what has stuck to it. By the time a handful of grain has been converted into a handful of fine flour it has gone through some 50 different machines, including 18 sets of rollers and 18 purifiers.

‘The following points may be of interest: A first-class London mill working 100 sets of rollers can turn out 45 sacks of flour per hour. Offal, according to its fineness or coarseness, forms bran, pollard, etc., and is worth from 5l. to 6l. a ton. The qualities of flour are whiteness and strength. The former is tested by the eye, the latter only really by baking capacity. There seems to be a general consensus of opinion in favour of flour made from Hungarian wheat. The best English is of sweeter flavour, but lacks “strength.” It has been reckoned that 300 sacks are made per hour in London mills, all of which is consumed in London. The flour mill industry owes nothing to American inventive genius; on the contrary, that country is behind the times. The steel rollers came originally from Hungary—always a great milling country.’