Very many instances of these mills may be given, but one will suffice, more especially as in this case it was carried down to modern times. There was at Wakefield, Yorkshire, a corn mill which was a franchise of the Pilkington family, of Chevel Park, by charters from one of the Edwards. The monopoly of grinding the corn at this mill was a great sore to the inhabitants, and the cause of much litigation, but the holders of the rights always came off the victors. They claimed the right of grinding not only for the town of Wakefield, but for some miles round, including the villages of Horbury, Ossett, Newmillardam, and others; so that115 all the corn used in this district was obliged to be ground at the ‘Soke Mill,’ or, as it was otherwise called, the ‘King’s Mill,’ and neither meal nor flour could be sold unless it were ground there. The tenant of the mill demanded a ‘mulcture’ of one-sixteenth—that is, out of 16 sacks of corn he kept one for himself for grinding the other 15.

Some time about 1850 the inhabitants of Wakefield and the adjacent villages determined to purchase the rights, and this was done by a rate spread over a series of years, and called the ‘Soke Rate.’ The purchase money amounted to about £20,000. The same kind of property existed at Leeds and at Bradford; but from neglect on the part of the owners, and lapse of time, the inhabitants turned restive and independent, and ‘broke the Soke,’ without compensating the Lords of the Manors. These mills are still called the King’s Mills.

Nor was this custom confined to England. In Scotland, in feudal times, it was common for the tenants of a barony to be bound to have their corn ground at the barony mill. Centuries ago the erection of a substantial building, with the millstones, driving machinery, and other plant necessary for a mill, together with the drying-kilns, mill-dams, lades, weirs, and watercourses requisite for a corn mill involved the expenditure of a considerable sum of money, such as only the baron could find. He, therefore, assured himself of a return for his capital invested by binding his tenants to use his mill. Of course, he got a good rent for his mill, which was the manner in which the benefit arising116 from the bondage of his tenants found its way into his coffers.

Sir James A. Picton, in his City of Liverpool selections from the municipal archives and records, states that in 1558 the Corporation of the Borough ordered that ‘every miller, on warning, shall bring his toll-dish to Mr. Mayor, to a lawful size thereof sealed, under a penalty of 6d.’ That this toll-taking on the part of millers was occasionally perverted there can be but little doubt, and it was sometimes very severely commented on, as we may see in this passage from a tragedy by Wm. Sampson (1636), called The Vow-Breaker; or, the Fair Maid of Clifton. ‘Fellow Bateman, farewell; commend me to my old windmill at Rudington. Oh! the mooter dish—[Multure or Toll-dish]—the miller’s thumbe, and the maide behind the hopper!’

In the Roxburghe ballads (vol. iii., 681) we have The Miller’s Advice to his Three Sons in Taking of Toll:

‘There was a miller who had three sons,

And knowing his life was almost run,

He called them all, and asked their will,

If that to them he left his mill.

He called first for his eldest son,

Saying, “My life is almost run,

If I to you this mill do make,

What toll do you intend to take?”

“Father,” said he, “my name is Jack.

Out of a bushel I’ll take a peck,

From every bushel that I grind,

That I may a good living find.”

117

“Thou art a fool,” the old man said.

“Thou hast not well learned thy trade.

This mill to thee I ne’er will give,

For by such toll no man can live.”

He called for his middlemost son,

Saying, “My life is almost run.

If I to thee the mill do make,

What toll do you intend to take?”

“Father,” says he, “my name is Ralph.

Out of a bushel I’ll take it half,

From every bushel that I grind,

So that I may a good living find.”

“Thou art a fool,” the old man said;

“Thou hast not learned well thy trade.

This mill to you I ne’er can give,

For by such toll no man can live.”

He called for his youngest son,

Saying, “My life is almost run.

If I to you this mill do make,

What toll do you intend to take?”

“Father,” said he, “I am your only boy,

For taking toll is all my joy.

Before I will a good living lack,

I’ll take it all, and forswear the sack.”

“Thou art my boy,” the old man said,

“For thou has well learned thy trade.

This mill to thee I’ll give,” he cried,

And then he clos’d his eyes, and died.’

To show the popular idea of a miller’s integrity, I may mention that the children in Somersetshire, when they have caught a certain kind of large white moth, which they call a Miller, chant over it this refrain:

‘Millery! millery! Dousty Poll!

How many sacks of corn hast thou stole?’

118

and then they put the poor insect to death on account of its imaginary misdeeds.

Even Chaucer must have his gird at the miller:

‘The millere was a stout carl for the nones,

Ful byg he was of brawn and eek of bones;

That proved wel, for over al ther he cam

At wrastlygne he wolde have alwey the ram8.

He was short sholdred, brood, a thikke knarre9,

There was no dore that he ne wolde heve of harre10.

Or breke it at a reunying with his head

His berd, or any sowe or fox was reed,

And ther to brood, as though it were a spade

Upon the cope right of his nose he hade

A werte, and ther on stood a toft of herys,

Reed as the brustles of a sowes crys;

His nose thirles11 blake were and wyde;

A swerd and a bokeler bar he by his syde;

His mouth as greet was as a greet forneys,

He was a janglere and a goliardeys12,

And that was moost of synne and harlotries,

Wel konde he stelen corne and totten thries13,

And yet he hadde ‘a thombe of gold’ pardee

A whit cote and a blew hood wered he,

A bagge pipe wel konde he blowe and sowne,

And ther with al he broghte us out of towne.’

The ‘thombe of gold’ has somewhat puzzled commentators on Chaucer. One thing is certain: that a miller has been traditionally credited with a broad thumb, and the little fish the Bullhead is called The Millers’ Thumb, from a fancied resemblance. Every one connected with the navy knows what the ‘purser’s thumb’ is, from the legend that, when serving out their 119tots of rum to the men, his thumb was invariably inside the measure (doubtless necessitated by the rolling of the old men-of-war), which resulted in a large profit to himself during a long cruise, and this seems to illustrate Chaucer’s meaning, especially as it occurs immediately after the miller’s ill-gotten gains, that by putting his broad thumb into every measure he made thereby gold during the year.

But there is another and a kindlier explanation of the term, which rests on the authority of Constable, the painter, according to Yarrell, in his History of British Fishes, when writing of the Bullhead. ‘The head of the fish is smooth, broad, and rounded, and is said to resemble exactly the form of a miller’s thumb, as produced by a peculiar and constant action of the muscles in the exercise of a particular and most important part of his occupation. It is well known that all the science and tact of a miller are directed so to regulate the machinery of his mill that the meal produced shall be of the most valuable description that the operation of grinding will permit, when performed under the most advantageous circumstances. His profit or his loss, even his fortune or his ruin, depend upon the exact adjustment of all the various parts of the machinery in operation. The miller’s ear is constantly directed to the note made by the running-stone in its circular course over the bed-stone, the exact parallelism of their two surfaces, indicated by a particular sound, being a matter of the first consequence; and his hand is as constantly placed under the meal spout to ascertain, by actual contact, the character and qualities of the meal120 produced. The thumb, by a particular movement, spreads the sample over the fingers; the thumb is the gauge of the value of the produce, and hence have arisen the saying of worth a miller’s thumb, and an honest miller hath a golden thumb, in reference to the amount of profit that is the reward of his skill.’

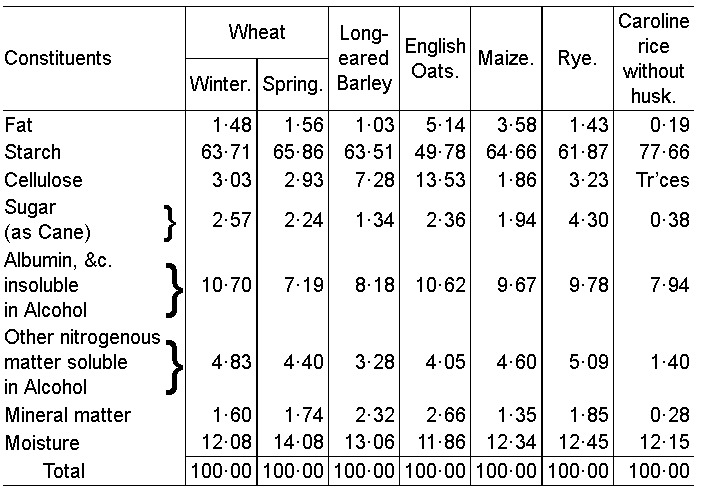

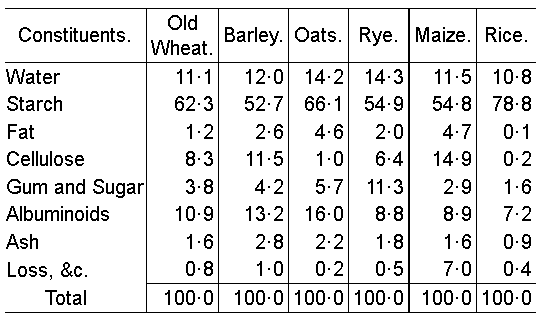

Any notice of flour would, of course, be valueless without an analysis of its constituent parts, which, as anyone can understand, will vary in different wheats; there can be no standard, because of the difference of the soils on which it grows, a fact which is fully borne out by the following tables by famous analysts. Jago (The Chemistry of Wheat, Flour, and Bread, &c. Brighton, 1886), quoting Bell, says:—

Professor Graham, in a lecture delivered at the International Health Exhibition, London, July 3, 1884, quoting Lawes and Gilbert, says:—

Messrs. Wanklyn and Cooper (Bread Analysis, &c., London, 1881) say that, according to their analysis, this wheaten flour, which is the flour commonly to be bought in this country, has the following composition:—

Water 16·5

Ash 0·7

Fat 1·5

Gluten 12·0

Vegetable Albumen 1·0

Modified Starch 3·5

Starch Granules 64·8

–––––

100·0

A comparison of these tables by well-known analysts shows us, if we only take the single article of wheat, how the grain varies. Let me now say122 something about the constituents of wheat in as simple a form as possible.

The fat is of a yellow colour, and, as far as is known, is not a particularly valuable component part; but as all fats are foods, of course, it is of service.

The starch in wheat is the ordinary starch (of the best kind) of commerce; and, seeing that it forms the greater part of all breadstuffs, it naturally is an important element in them. In good, sound wheat the starch granules are whole; in sprouted wheat, or that heated by damp, they are rotted, and, consequently, the starch they contain is changed, more or less, into dextrin and sugar, and, consequently, a difference is made in the food value of the wheat.

Dextrin and sugar are small components of good wheat. The dextrin, no doubt, has a beneficial effect in small quantities, but not in large. Sugar, such as is found in wheat, affords the necessary amount of saccharine matter for fermentation.

Cellulose is more useful to the plant than to the miller, to whom it is as so much bran.

There are two kinds of albuminoids, or gluten, present in wheat—one insoluble, the other soluble in alcohol. The former makes what is called a ‘strong bread,’ and the latter acts, in bread-making, on the former, and, under the influence of yeast, it attacks the starch, converting it into dextrin and maltose.

The ash of wheat contains principally phosphoric acid and potassium; magnesium ranks next; then lime, silica, phosphate of iron, soda, chlorine, and sulphuric and carbonic acids.